Few people enjoy the incredible staying power of French Lessons’ final profile this season. But before we (re-)introduce her, please allow us a small indulgence.

Let’s first wander back through the highways and alleyways, the shops and vistas we visited this summer. Through our “interviews à la Colbert,” we met people with unique perspectives on Antibes, our summer hometown on the bustling Côte d’Azur. Thanks to their personal stories, we glimpse hidden layers in this place:

- The glamorous Christelle shared tales of power and crime from her driver’s seat of an executive taxi.

- Caroline, the artisanal framer, restored a relic of our quirky villa while extolling the virtues of authenticity.

- Judy, the town’s top-rated Vrbo host, took us behind the scenes at her beloved, seaside rental apartment.

- And – we couldn’t help penning this note – our favourite pet Yoko shared her exasperation at a bout of French toilettage.

As we travel through these posts, we thank you for joining us (again) this season. We absolutely delight in the growing community among French Lessons readers – the way an article prompts someone to post a comment that sparks a thought from another reader, often on a different continent. We say a gros merci to this beautiful society and look forward to next season when our community – from office chairs, exercise bikes, and sun loungers alike – can share some moments together in the Mediterranean sun.

In our final profile of the season, we spotlight a figure who spans generations in Antibes. Madame Lucienne Frey first set foot in town when she was 33 years old, and French Lessons had the joy of interviewing her on her centenary. To cap this season, we repost that interview – a firm favourite of ours – to mark the recent passing of an extraordinary woman, aged 108.

***

These days I’m très fière – very proud – to tell people my age, Madame Lucienne Frey says with an easy smile. They celebrated my 100th birthday at the mairie this spring. The mayor, who I know a bit, gave a reception.

Mme Frey is pleased with her newly acquired threshold – yes, certainly – but she’s not overly charmed by it. She hardly lets age define her.

I told the maire there are a lot of people who reach 100. Why celebrate me? she wondered. She sits before my husband Philippe and me, a willing audience, in an easy chair. Her soft grey, cotton dress is offset by a long, artistic strand of salmon, charcoal, and grey stone beads. That salmon colour coordinates perfectly with her lipstick and low leather pumps. Her eyes are alert, and her thick hair is pulled back loosely. She is, quite simply, beautiful.

The maire told Mme Frey they were celebrating her because not all 100-year-olds arrive at this age in quite the same shape. And he was hardly the first one to notice.

Mme Frey mentions her cardiologist. There’s little hesitation in her speech, no predictable pause as her elderly brain reaches for words. She easily shares with us her cardiologist’s big hope: He told me that if he could figure out a way to live to 100 like I have, he’d sign up in a second.

The first time I met Mme Frey, people around me were more interested in her son-in-law. Robert Charlebois is French-Canada’s answer to Bruce Springstein. Philippe knows him from Quebecois circles. A couple summers ago we invited Robert and his wife Laurence for aperitifs on Bellevue’s terrace. Who’d they bring along but Laurence’s elegant and quick-witted mother who lives up the road.

As we sipped rosé and nibbled on olives, a handful of swimmers on the rocky beach below Bellevue turned their attentions toward our balcony, snapping a few shots when Robert moved to the railing. Well-known as the son-in-law may be, the real star to me that early evening was Mme Frey. I was in the throes of researching Bellevues’ history and voilà, here on my own terrace was living history. I dove in for her insights – only then guessing she must’ve been in her eighties, and still I was too low.

With anniversaries of the World Wars overtaking the airwaves and bookstands, I was keen to contact Mme Frey again. That’s how Philippe and I find ourselves not far from Bellevue, in the centenarian’s gracious salon overlooking the neighbouring gardens.

Laurence and the famous Robert helped us find her this time – as did a few locals. Everyone seems to know Mme Frey.

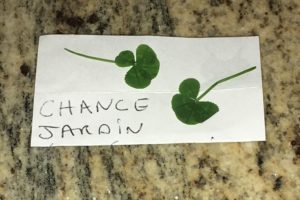

Are the flowers for me? An earnest-looking man asks as he mounts his scooter this morning. We’ve gained access to Mme Frey’s gated community but are none the wiser where to find her.

Tout au bout, the earnest man says when he learns of the destined recipient. He points straight ahead.

Philippe and I stop at the end of the lane. A man sits on the steps of a well-maintained apartment block with two young girls. We ask for Mme Frey.

La centenaire! He says. He buzzes us in. Second floor, he tells us. First door on your right. I’ll ring her for you.

Mme Frey’s sitting room is a jewel box of photos and collectables – a gathering of precious memories but hardly uncontrolled bric-a-brac. A few paintings line beige walls while rows of framed photos spread over bookshelves that contain French literary titles and travel books. Occasional tables and chairs dot the room, as does a handsome inlaid bureau with more photographs on top. Most of the far wall opens onto a terrace; a gentle breeze blows in through pastel-striped, silk curtains.

Something to drink? Water? Mme Frey asks from her easy chair. Un petit pastis? It’s 11:20.

Un pastis! I say. I ask if she drinks this strong, local brew.

Non, not now. Only in the evenings, she says. And mixed with a good bit of water.

Philippe joins me today out of courtesy and interest and, it must be said, to help me grasp the fullness of this French discussion. I can keep up with the broad brushes, but I fear missing the detail – or else inhibiting Mme Frey’s thoughts by asking for clarification.

She surprises us both by offering to speak in English – in English. Her diction is beautifully clear to my Anglophone ear.

I spent the war years in New York, she says. My mother was only 20 when I was born, and she panicked at the idea of war. When my father mentioned New York, she jumped on the opportunity.

It takes Philippe and me a while to realize that Mme Frey is talking about the World War I years. That’s the only way this story makes sense. Surely the young family travelled across the Atlantic by boat (and only a couple years after the Titanic disaster). Mme Frey spent five years in New York before returning to Paris, probably again sailing the seas.

I came back speaking French with an American accent, she says. The kids made fun of my accent.

I nod, knowingly. These days the American twang in Mme Frey’s voice is gone, what with a year at an English boarding school, aged 16, and all those intervening years of life since her earliest days in the US. She slips back into French.

Mme Frey met her first husband on a train from Marseille to Paris. She was 24 years old, travelling home with her mother and stepfather. They’d bribed her into joining their winter holidays in southern France by allowing her to drive the family’s car. On the return journey the family put the car on the train and waited on the platform. And waited. When was the train coming? they wondered aloud to each other.

A man in a pink shirt materialized from nowhere and joined their conversation. The train was delayed because of snow, he said. Once on board, it turned out that his compartment was next to theirs. The train departed Marseille, and this man and the young Mme Frey moved from their seats into the corridor to talk.

I spent a good portion of the trip trying to figure him out, she says. He wore a pink shirt, and that wasn’t so doable in those days!

The couple stood the entire journey back north, when at last the pink-shirted man asked if he could take the young lady to lunch. It was 1938 in Paris. A second World War would imminently cross Mme Frey’s path. Still the new couple dined together and went to the cinema. Shortly they got married.

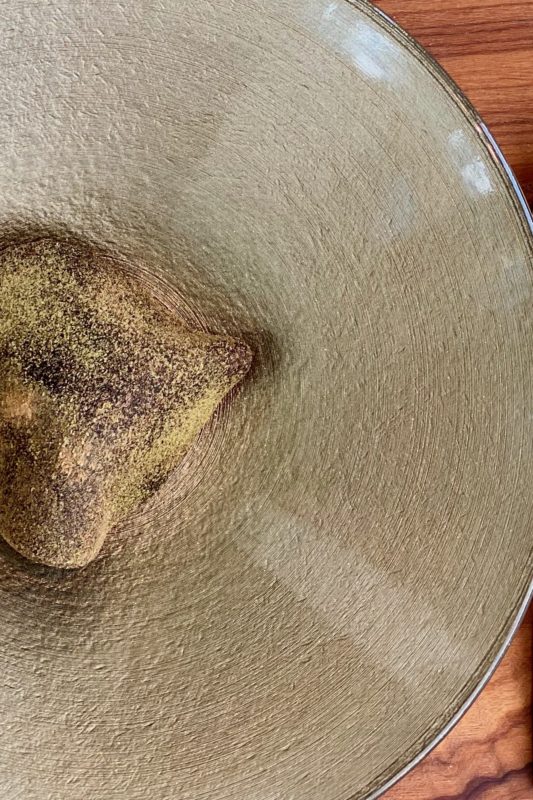

In 1939, on the very day war was declared, Mme Frey’s new husband told her to go out and buy every pair of shoes she’d ever wanted. I’d been eyeing a fancy pair, she says, but they were very expensive. He said to get them anyway. I wore those shoes for a very long time.

Just after France’s Occupation, an estate agent friend encouraged Mme Frey’s husband to buy a house in Antibes. It was très bon marché, he was told – a good deal. They should buy the place as an investment.

So in 1947, during that nebulous period between the inauguration of wartime monuments and the re-launch of the Cannes Film Festival, the couple bought this house – sight unseen. It was in the Garoupe, a wooded area beneath the rubble of the Cap d’Antibes’ yet-bombed-out lighthouse. Mme Frey journeyed south, alone, to glimpse their purchase.

There were so many pines, she says. You had to chase the sun across the garden because the pines made too much shade.

She shares her shock when several years ago her daughter took her on a drive around the Cap – a so-called trip down memory lane. They discovered the house no longer existed.

It was a construction magnifique – solide, confortable, Mme Frey says, still half-reluctant to believe in its demise. The neighbour bought the property, demolished the house, and built a workout room.

But you don’t want to hear just about me! she says, years of refined living eclipsing any notion of a captive audience. Tell me about you. She hands out polite compliments to me, the biggest one probably being that I’m young.

But I want to stay young like you, I insist. You must have very good genes.

Yes, Mme Frey, says. She has good genes. But it’s also une question de morale. The bottle is always half-full, she says. She uses that very metaphor in French.

Still, she admits to missing golf. She used to play regularly at the local course in Biot. It took only 10 minutes to get there, she says, but today it takes 30. If only she could manage a little golf! But, she says with a good-natured laugh, how do you do it with a wheelchair? (During our visit Mme Frey walks around her apartment with a cane, but the distances are well shorter than 18 holes.)

Golf was her main sport. Waterskiing and tennis were the others. I’m très indépendante, she says. I played tennis but only en simple, never doubles. She has no problem losing games through her own mistakes, but she hardly wants to depend on a partner.

Good genes, a solid morale, and a strong sense of independence, I think. That’s what the cardiologist needs to reach 100 years of age in such great shape. That’s what I need too. That’s what we all need.

At the time Mme Frey first came to the Cap d’Antibes, she was in her early thirties. Paris was still home, but with her husband and two daughters she began to travel here for holidays – Easter, summer, and Christmas. She didn’t move to Antibes until 1994, aged 80, when her second husband died.

Je n’ai jamais regretté ce choix, she says. I never regretted that choice.

Mme Frey remembers that early vacation home in the pine forests of the Garoupe. We bought a Christmas tree that reached up to the ceiling, she says. It was a custom she adopted from her earliest years in New York. Eventually, though, the shadowy, pine-filled garden got the best of her. On the advice of another real estate agent, Mme Frey’s family bought a different home in the area, this time on what was a small, dirt path at the top of the Cap d’Antibes.

It was a large home on Chemin de Mougins, she says. We had three stories, a pool, a gardener, and a super view. Her clear, dark eyes sparkle through stylish, two-toned frames as she remembers this last feature. When I first walked into the house and saw the view, my heart skipped a beat. You could see all the way to St Tropez.

After the death of her first husband, Mme Frey met the man who’d become her second at a dinner event. He was grand, bien et beau, she says – tall and good-looking. They sat side-by-side at a table of 10, the seating having been pre-arranged by the host. And on this sociable occasion she posed a simple question to this handsome man: Why are you so sad?

Years later, after the couple married, Pierre Frey said he was struck that she was able to see so clearly into his heart. He was charmed by her insight and fell instantly in love.

So the list again extends itself. Alongside good genes, a positive attitude and a fierce independence streak, and maybe a strong second language to boot, you need special insight in order to live a long and full life.

This Mr Frey, it turns out, was the founder of the luxurious French fabrics house bearing the same name. Having originally established his company in the north of France, he lost everything with the German invasion. But he started again, the second time in post-war Paris, and thanks to a son and three grandsons from his first marriage, the business continues to carry his name today.

Mme Frey’s only input into the esteemed fabrics company was to choose colours for the new season. Mr Frey would bring colour swatches home to his wife and rely on her choice.

That’s one thing I always had was good taste, Mme Frey says. Her words come without an ounce of boastfulness. She’s simply stating a fact. Glancing around her graceful salon – and again noting her coordinating salmon lipstick, necklace, and pumps – it is clear that colour and taste remain important in her life. Even at 100 years of age.

Drat. We’ve discussed genes and attitudes, language, independence, and insight. Now we also need taste.

On our way out, Mme Frey takes Philippe and me on a brief tour of her salon. There are countless photos of family – here as children, there with their own children, and there as they all celebrate her 100th birthday. On the bureau there’s a photo of a friend with Winston Churchill. Tucked inconspicuously into the corner of the room is a small, console piano.

It’s from Robert for when he comes to say, Mme Frey says. He asked if I wanted a piano, and I told him non, not really. It takes up space. So he said not to worry. This one is small and white and blends in with the furniture, so I’m okay with it.

On our way out, I notice a game of Scrabble on her table. Two wooden trays of letters await their next turns. L’Officiel Scrabble dictionary lies on the wooden table beside the playing board, as does a fat Petit Robert dictionary and a good magnifying glass.

Do you play Scrabble? I ask.

Oui, Mme Frey says with evident glee. I play two hands at the same time, she tells me. Both hands by myself. This way I can’t cheat!

The Scrabble board itself, I realise, is a symbol of her grace. Through it, Mme Frey applies her powers of language, independence, and insight. And she pours them from a vessel that’s always at least half-full.

Follow us on Instagram @frenchlessonsblog