When four parchments appeared in a British auction house two months ago, the city of Antibes was “in the room” – virtually speaking, anyway, amid this public health crisis. The city’s bid was backed by the deep pockets of the Sovereign Prince of Monaco.

The documents up for sale were presumed lost forever: Their whereabouts had been unknown for seven centuries. But on May 28, 2020, the day of the auction, the city of Antibes and its princely ally won the bid, and shortly afterward the parchments arrived – one could say – back home.

The association of Antibes and Monaco royalty has indelible roots. The House of Grimaldi, founded in the 12th century, were pivotal players in the history of the Republic of Genoa, and in the Principality of Monaco, where the dynasty has reigned to this day with Albert II, Sovereign Prince of Monaco, as its current head. One of the oldest feudal branches of the house, the Grimaldi d’Antibes, once ruled this city from its seaside castle, the prominent château that today houses the well-known Musée Picasso.

Now settled on home ground, the old documents are the new toy at Antibes’ Archives Municipales, but no one is coming to play. Literally no one. When I arrived at my dutifully reserved créneau for a solo look at the prized parchments, I was, by design, the only visitor inside the archives. But Emilie, my manager-friend at the agency, told me that, non, she and her colleagues were not swamped with bookings. In fact, I was the first.

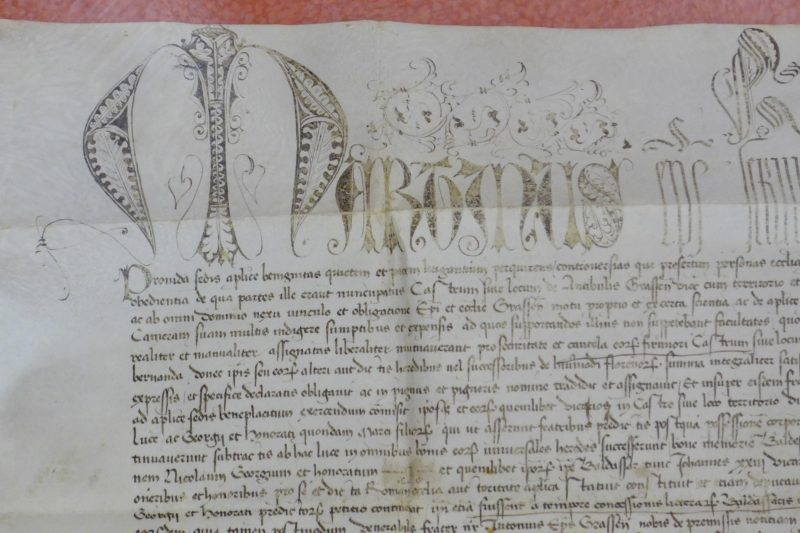

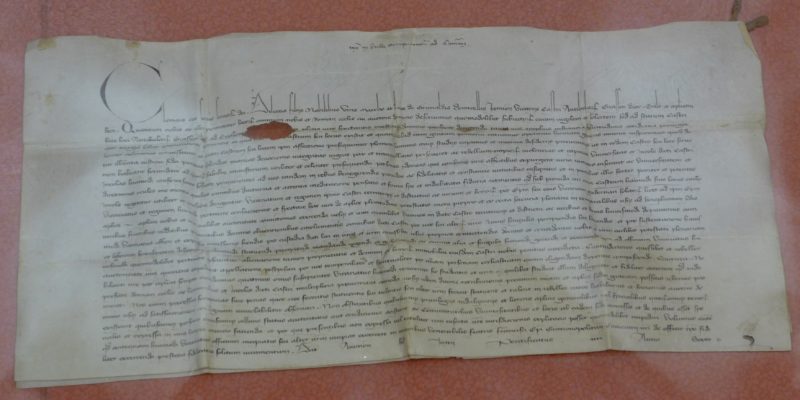

Which is shocking because the new toy is a collection to behold. The calligraphic art of the documents’ Latin words, ink on vellum, is itself enchanting. Each letter is a blossom, beautiful and delicate in its own right; the first line of calligraphy on one document blooms into a two-dimensional objet d’art. The craftmanship becomes even more impressive after remembering that the ink was laid onto the vellum using the tip of a long, straight, goose feather. Without the convenience of Wite-Out or a backspace key.

To convey the allure in another way, this acquisition represents the only known parchments coming from the archives of the Grimaldi d’Antibes line. They are worth seeing.

The oldest of the four document dates from 1381 and relates to an important inheritance (involving more than one castle) by Katherine, daughter of Marc de Grimaldi, from her maternal grandfather. (Marc de Grimaldi – keep reading – was a key figure in the Antibes branch of the Grimaldi family.) The lettering of this document is arguably the most beautiful among the four, with its initial word invoking a frenzy of flourishes and filigree.

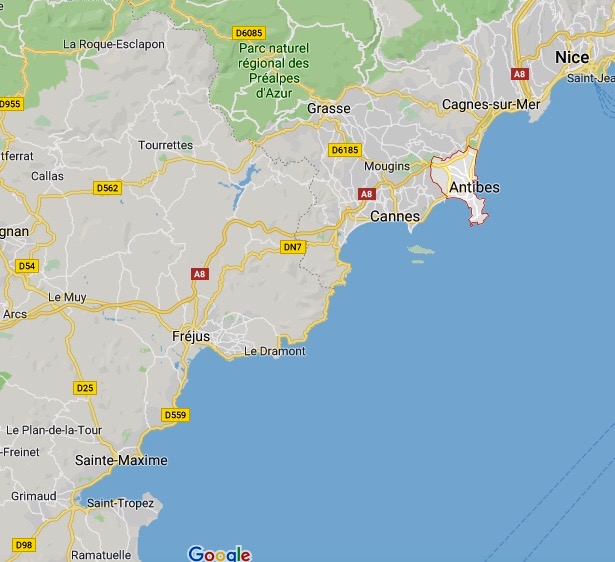

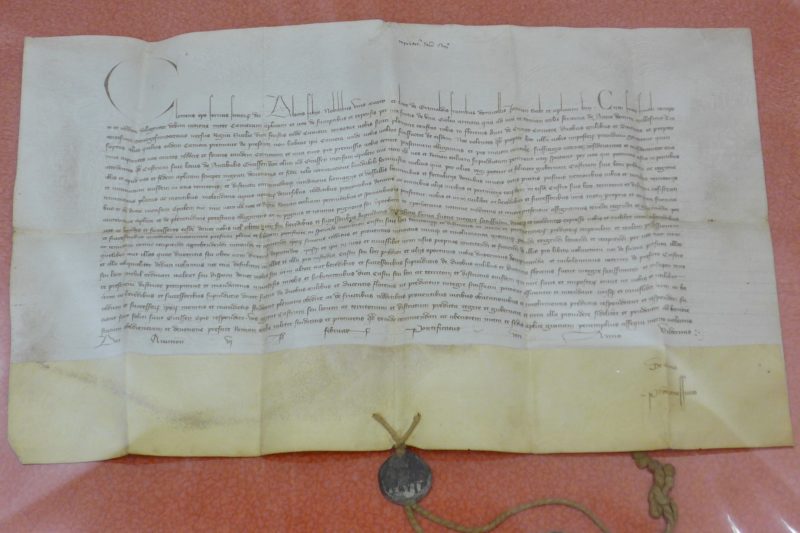

It’s the next two parchments, though, that interest me most. In the document dated 1384, Antipope Clément VII grants the brothers Luc (c. 1330 – 1409) and Marc (died after 1396) de Grimaldi rule over Antibes’ castle, once they take an official oath of office. For context, it was a time of religious and political turmoil, and Antibes’ château itself had been hit by violence and plundering by impious rebels. The Catholic Church recently had divided, with two (and later three) men simultaneously claiming to be the true Pope.

Antipope Clément VII was the first in a line of antipopes. Installed in Avignon (France), he relinquished Antibes’ castle and its rights in order to reduce his debts to the two Grimaldi brothers. Clément VII was in constant need of funds, and the sale of this château had involved some fancy financial footwork. Before arranging the disposition, the antipope had removed Antibes from the portfolio of the bishop of Grasse, thereby bringing the territory back under the jurisdiction of the Papal Treasury. The move, we will see, ruffled more than a couple goose feathers.

The third document, dated 1390, relates back to the sale of Antibes’ château. Having settled other accounts, Antipope Clément VII still owed money to the two Grimaldi brothers. Viewed with modern eyes, the financial mechanism is muddy, but this third parchment discloses that Clément VII raised a sum of 2200 golden florins (1.48 million euros) by mortgaging Antibes’ castle – which already belonged to the Grimaldi men to whom he owed the cash. Emilie, my friend at the archives, believes that this 1390 document may serve to clarify the 1384 transaction. Fourteenth-century administration, she quipped, didn’t happen at today’s lightning speeds.

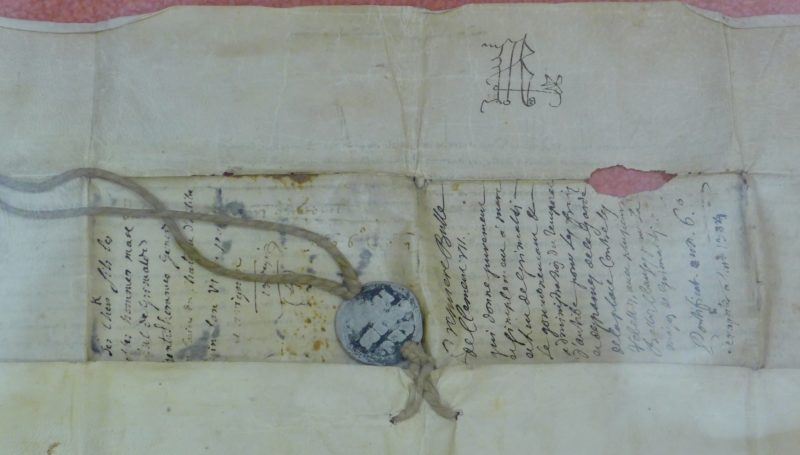

The script of these first three vellums has a painstaking, ruler-straight uniformity and legibility, indicating that their business was official and public. These documents were meant to be read by many. The transactions involving Antibes’ castle and its mortgage also carry a papal seal still attached to each record. Having read about the seals beforehand, I’d imagined them to be wax – but they are solid lead. At one point during my visit to the archives, I held a mass of silk threads knotted to a third Clément VII medallion that also came with the auction lot, and I estimated it to weigh about a pound. The seal pictured below remains fixed on the reverse side of the 1384 parchment, beside a more hastily scrawled note:

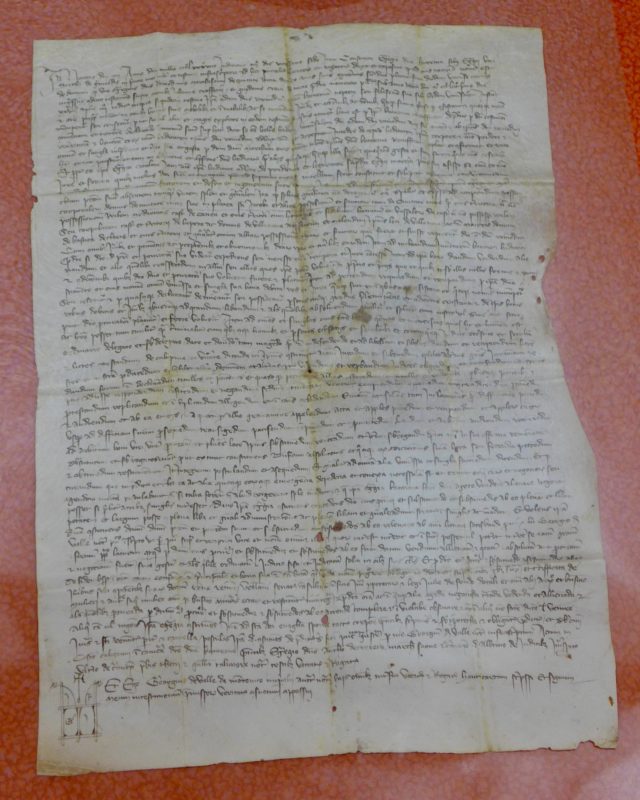

The last parchment, dated a youthful 1431, bears evidence of a continuing quarrel over who holds the keys to the castle. Written in Rome, the decree by Pope Martin V settles a dispute between the Grimaldi family and the bishop of Grasse by declaring that the sons of Luc and Marc de Grimaldi – Nicolas, Georges, and Honnorat – and their heirs, own Antibes’ castle. The writer of this document, likely a notary, took less care with his calligraphy, implying that the words were for administrative or professional (and not public) purposes, but this parchment creates a decisive and satisfying exclamation point to the collection.

Antibes’ won the British auction with a bid of 5,600 pounds (8,031 euros), but in another sense, the four parchments are priceless to the city’s heritage. When they arrived home, the documents were folded into a small box. Emilie, preserver of Antibes’ heritage, was stunned at the cramped packaging. The team at the archives has since released the documents and slid them within clear plastic coverings, but the outstretched pages bear creases of a lengthy confinement. The next task is to study the pages, possibly transcribing and translating their texts, but it’s a lofty goal. The vellums are written in Renaissance Latin.

Being legalese, we cannot expect to discover philosophical awakenings or jaunty turns of phrase with the translations, but with Emilie’s help, I already could discern the flux of Antibes’ own name. I’d come to the archives that day with a separate question. The town had begun life under the Greeks as Antipolis (meaning “the city opposite” from (at that point) Nice or Corsica). In the Middle Ages its name morphed to Antiboul, and sometime afterward – when? – Antibes gained its current name.

Emilie pointed out a beautifully formed Antibuluef in the newly-acquired 1384 parchment, and an Antibul in the 1390 one. The words could be proper nouns or adjectives or some other form entirely, but scholars now have another means to unravel the city’s past.

Time also has moved on for Antibes’ château. In 1608, Henri IV (also known as Good King Henry) recuperated the castle for the French crown. Since then, the space has served as a residence for royal governors, a town hall, and an army barracks, until the city of Antibes bought the castle at auction in 1925 for 50,000 francs (7,622 euros). The storied building next housed a local archeological museum before serving as Picasso’s studio for several months after the war, and eventually becoming the art museum that bears his name.

“Will the archives try to figure out where the parchemins have spent the last centuries?” I asked Emilie.

“C’est très difficile,” she said. There’s nothing written. The Grimaldis – assuming the parchments stayed within the family – are very spread out. One thought is that the documents entered a private English collection through the inheritance of a French parent at the beginning of the 20th century.

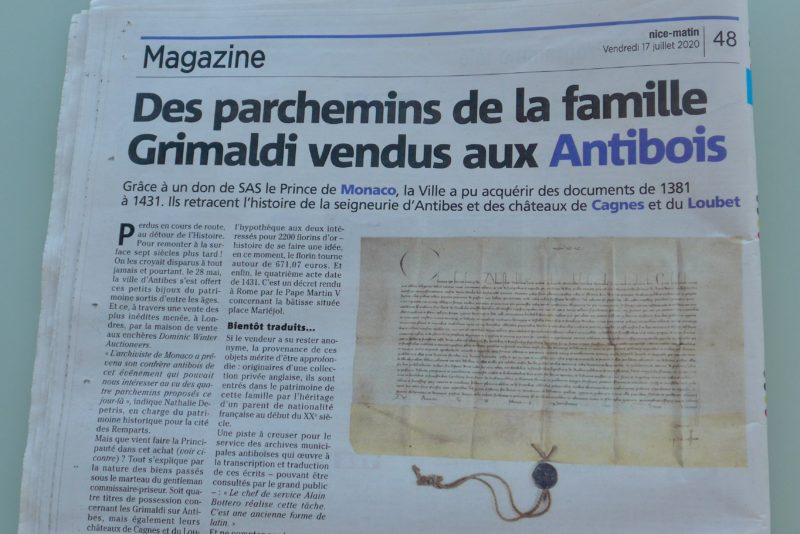

Will more visitors reserve their créneaux to glimpse the latest acquisitions? The documents’ arrival has filled the back page of the Nice-Matin newspaper and has been publicized among local sociétés. A royal visit also would heighten their profile. Prince Albert II is apparently interested but his agenda is full.

Hopefully, if a royal rendez-vous ever materializes, the Prince won’t be Visitor #2.