Philippe says this post isn’t funny enough. He thinks only musicians will appreciate it. My husband casts his eye over most French Lessons articles before I hit “Publish,” so his reticence does give me pause. I’m hoping these lines give some insight to France and to a less-trodden world within this country. I’m hoping it offers a couple French Lessons, so to speak, even if there are fewer laughs. To publish or not to publish? I leave you, dear readers, to decide.

*

French Lessons has stumbled on Hogwarts School of Miraculous Strings, and it’s right here in the heart of the Côte d’Azur. How surprised and charmed – and humbled – we are . . .

“The cello matter is more complicated than I thought,” a local friend emailed right before my family and I arrived in Antibes for the summer. Violeta had left three messages with a personal contact, and finally his shop called her back to recommend two others. The quick search for a suitable cello was becoming a job.

Violeta, I should say, is an internationally acclaimed violinist. Just writing that makes me happy. We met over a decade ago through our then-toddlers, and for a good while I had no idea she knew an F-sharp from an A-flat, but over the years we’ve become firm friends. “I am absolutely positive that we will find something,” she wrote. Her usual optimism would propel the search.

I’d expected a few problems renting a cello for the summer in the Cote d’Azur, especially as I wanted a 7/8, one that’s a bit smaller than full-sized. It’s what I’ve been playing on this musical journey that began last autumn as a brain-boost – as a way to keep the grey matter from shrinking – and as an encouragement my 13-year-old Lolo, whose interest in her own cello has plummeted. Now as fate has it, only one of us cares about maintaining her cello knowledge over the lazy days of summer. That would be me.

Shortly after arriving in Antibes, Philippe, Lolo and I have a rendez-vous at the obliging strings shop in nearby Nice. Violeta found a 7/8 cello, and while short rentals are expensive (like everything else in the Côte d’Azur), the shop calculated its best price, and it was hardly outrageous.

The news seemed too good, so I’ve been preparing myself. Renting anything – an apartment, car, pair of skis, designer handbag, or cello – is an onerous process. You skim the contract, knowing you should concentrate on the abundant and confusing words. You never know. You could be agreeing a worse price, crushing insurance, or automatic renewals to the end of your days. Imprisonment, even, in the case of loss, damage or theft.

Bad as that sounds, this cello document will be written in French. On average, French text takes 20-40% more space than English does. How many pages will the rental contract run? And if I’m still learning regular French words, how will I understand legalese?

As Philippe navigates eastward on the regional motorway, my brain amps up a notch. This is the Côte d’Azur. If words are an issue, inventory is a bigger one. So is my negotiating stance in a place where the customer can be more nuisance than king. I start wondering aloud to Philippe. Will the not-outrageous rental price agreed to Violeta immediately soar when the shop assistant hears my tourist’s accent? What if we still need to negotiate a bow and a case?

A more imminent problem is parking in Nice’s old town. Finding a spot within the same postal code is important when you’re collecting a cello. Now that we’re in the neighbourhood, cars are double-parked – they’re actually double-parallel parked – along the curb.

Is this when the magic begins? Old Nice’s traffic frenzy disappears with the wave of an imaginary wand. Two blocks from the stringed instrument shop, we find a parking space. A short walk later, café tables spill into a square shaded in broad-leafed trees. Customers sip espressos while others pass time on wooden benches. And there, a backdrop to this bout of serenity within the bustle of old Nice, lays a yellow storefront with whimsical, curlicue lettering, “Lutherie, Archèterie.” Stringed instrument making, bow making.

Philippe, Lolo and I file into the shop. I swear J.K. Rowling should be scribbling notes at a corner table, drawing inspiration for her next series. Violins, violas, cellos and their constituent parts inhabit the walls, bureaus, and floors. Rows of violins and violas hang in a glass-windowed cabinet adorned with stringed instrument scrolls. The tattered face of a bass forms a wall hanging. A whole instrument – too small to be a cello but too large to be a viola – hangs on another wall.

It’s a 1/32 cello, an attendant explains.

We introduce ourselves. “We have a rendez-vous avec Jean,” I say, my accent screeching Anglo-tourist. “I’m here to rent the 7/8 violoncelle for the summer.”

The assistant does not flinch. Instead Jean magically appears, and we follow him and the thin braid of his tawny hair down into a windowless cellar. My eyes adjust to the darkness of electric lighting; cool air settles on my skin. Side-lying cellos clutter the floor like ranks of soldiers. Upright ones line the back wall, where violins also slot into post-box-style cubbyholes.

Our host holds a 7/8 cello by its neck and strikes a tuning fork. An A pitch reverberates gently through the space. He makes a few adjustments and offers me a bench set at the center of a red Oriental rug. It’s a makeshift stage. I must try the instrument.

I stiffen. “Donc, um, j’ai commencé jouer in the month of October,” I say, making excuses. I am learning. I take the instrument’s neck in my left hand and settle on a bench, wishing my small audience would click their heels three times and disappear.

Jean offers me a bow, and I take it in my right hand. The wood and horsehair are featherweight compared to my first rented bow. It’s a delight in my hand.

“I’m a learner,” I say, struggling with what to play.

“Best to start with une gamme (a scale),” Jean says, his voice gentle, “to see how the instrument sounds.”

I choose D major, starting on the cello’s middle string and bracing myself for the looming G, the fourth note of the scale that always comes out flat or screechy and lacking in all decorum.

The G is beautiful.

“You’re not in the middle of the bow highway,” I hear Lolo say as she watches with reluctant curiosity. “Your bow is travelling.”

I won’t acknowledge these imperfections. Instead I move to the low D, one of the cello’s deepest tones. Bowing the note, it vibrates through my fingers, my ribcage, and my knees as they brace the instrument’s body. I scramble to remember the fingerings, climbing two octaves and descending in arpeggios.

Wow. This cello bears no resemblance to my first rental. How quick I’d been to worry.

“You’re way too tense.” That’s Lolo again, trying to puncture my bubble. She’d rather be anywhere than a cello shop.

Now what? Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star comes to mind. Okay, no. Seriously.

Schumann’s The Happy Farmer? It is a work-in-progress. It wouldn’t sound at all happy.

I start playing Happy Birthday by ear.

What? I’ve never played Happy Birthday on a cello.

“Mom,” Lolo says in a way that only a teenager can address her mother. “It’s not anyone’s birthday.”

It doesn’t matter. I am besotted.

Jean, we learn, built this violoncelle. He actually created it. It was his first instrument, completed in Paris over the course of his final year of studies. These days it takes him 1.5 or 2 months to make an instrument, but this one took him a whole year.

He made the cello for his sister. This fabrication of wood and string has a story. Can my love grow stronger? With soft-spoken pride, the luthier reveals that his sister is a professional musician. She played this cello for a good while before asking Jean to make her another. She shifted indecisively between the two instruments before settling on the newer one, but felt badly that this violoncelle lay dormant. She insisted Jean rent it out if there was demand for a 7/8.

Jean offers to show us the atelier, and we accept. Together we return to the main floor, where a man now plucks the strings of a bass, and continue climbing to the workshop above the shop. Fresh air and daylight filter through open windows into a space crammed with stringed instruments, their parts and their tools. Art meets science. Precision drill bits meet 17th-century chisels. Time slows. When Rowling finishes jotting her notes below, she must get herself up here.

An apprentice carves a wooden violin scroll with a chisel. She works under the glow of an intensity lamp, her silence expressing both absorption and devotion. Across the narrow room, Jean fits my summer violoncelle with a missing fine tuner. At this point, I mention my long friendship with the revered violinist who connected us.

“It’s because of her that I wanted to find a better instrument for you,” the luthier says.

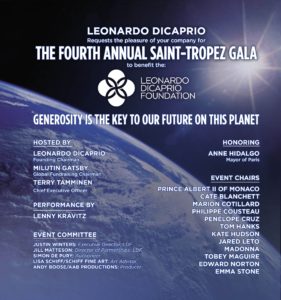

A shard of the modern day pierces the old-fashioned atelier. I should have known. Violeta’s friendship has smoothed the way for me. It’s helpful to have a personal reference in almost any situation, but nowhere is it more valuable, we have come to learn, than the Côte d’Azur.

An hour after Philippe, Lolo and I arrived at Hogwarts School of Miraculous Strings, the only remaining hurdle is the rental agreement. Back on the main floor, a single page lies on the front desk. It contains only the pertinent information; there is no fine print, no opt-in or -out over insurance, no mention of damage or renewal or incarceration. This cello’s replacement cost, I note, is nearly seven times that of my original instrument, but the rental fee bears no such relationship. And my summer cello package in the Côte d’Azur includes a bow and a case – and a tin of the finest rosin. Not only am I enchanted. I am humbled.

The four of us – Philippe, Lolo, my violoncelle and I – begin to wind out of Nice’s old town. Real-world chaos returns as we pull away from the Côte d’Azur’s own Hogwarts and its magical aura. Soon traffic snarls at a five-way junction. A man is pushing his broken-down sedan through the wide crossroads. Under the blazing sunshine, his feet grip the pavement as he bends sideways over the steering wheel, inching the vehicle forward. The chap toils alone – alone, that is, until another guy strangely materializes at his side.

The helper is wearing a motorcycle helmet. And strapped to his back is the hulking black case of a cello.