Last week I did something I’ve wanted to do all summer.

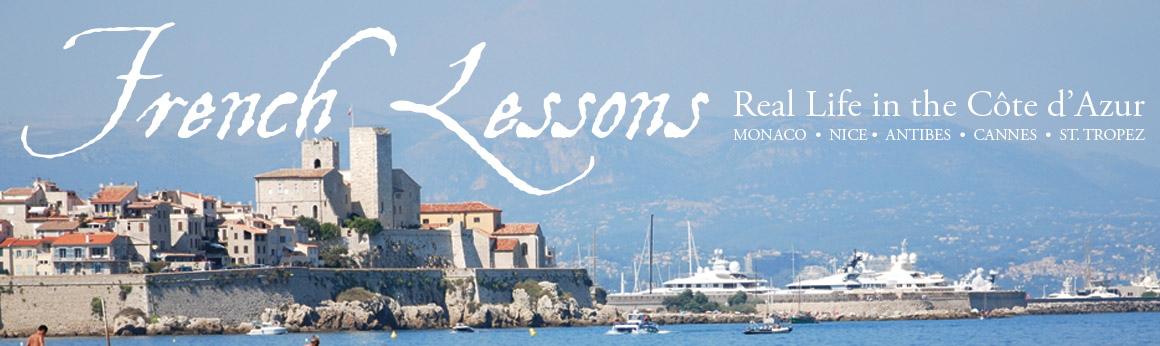

There’s a lone bench at the end of l’Ilette peninsula, a small piece of land that juts into the Mediterranean Sea near the end of Antibes’ old rampart walls. The bench faces the bay, looking out onto Old Town, and if you peer over your right shoulder when seated there, the Cap d’Antibes. Smack in the middle of that view of Cap d’Antibes is our home, Bellevue.

Below the bench on l’Ilette peninsula, the sea rolls onto a rocky outcrop that, at least this summer, is home to a wakeboarding shelter. At the base of the peninsula on the right side is the reasonably upscale Le Royal Beach restaurant.

But these things, you would say, are new additions.

The bench itself is basically two slabs of white cement. Behind it stands a tall shard of limestone with a plaque on it that has gone green, as copper does, with age. What I wanted to do all summer was quite simple: to read a particular book, or at least a section of that book, sitting on that particular bench stationed nearby that particular monument. So there I sat a short while ago, bicycle parked on my right, water bottle on the bench beside me, book in my lap.

Being the height of the August holidays, it was hot. The sun scorched down out of the late morning sky. As I tried to enjoy the experience I’d longed to savour, all I wanted to do was dive down to the Royal Beach restaurant and continue reading under the shade of an umbrella, drink in hand. But I could hardly do that. I was due to meet a friend there for lunch later. And anyway, more importantly, they’d suffered here on l’Ilette peninsula. There was no reason I shouldn’t do so, too.

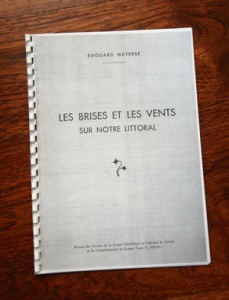

I leafed through the book to remind myself of its context, squinting through my sunglasses as the sun bounced off its pages. Duel of Wits by Peter Churchill. That I’d even found the text was pretty amazing. I’d originally come across a summarized version in French, buried somewhere in the museum website of Nice’s Musée de la Résistance. The book had been translated from its original English, I later learned, under a wholly different title.

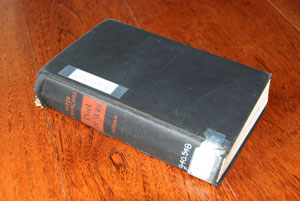

But last winter, as I sat in Toronto researching the details of life in Antibes more than a century ago, one thing led to another. Searching online, I found a secondhand copy of Duel of Wits at a community college somewhere in Indiana. It was pretty beaten up, I understood, but I bought it anyway, for $1.99 plus another $1.99 shipping. When the book arrived in Toronto, I packed it away for summer in France. I already knew the part of the story that interested me most, having read it online. I’d save the full story, in its original (and my original) English, for Antibes.

So there I sat in the mid-August sunshine, on a cement bench with a navy hardback book having the reference number 940.548 CH taped onto the base of its spine. Published in 1955, this copy was marked with stamps for the libraries of Scott Community College and Palmer Junior College. Flipping its pages brought forth a wholly familiar smell from my youth – that musty paper scent you find in old books, and especially in those sorts of books that have oodles of facts to impart to any chance reader. The scent cut straight through the expected smells of the seaside – sea and salt and sweat – and beckoned me into another world.

Churchill had dedicated his work to Arnaud – the code name for the late Captain Alec Rabinowitch, a radio operator – and to his underground contacts who, like him, had died in their pursuits.

On the next page, the author explained that his writings covered his four secret missions into wartime France, which he entered twice by submarine and twice by parachute. The stories began in July 1941 and ended in April 1943. All the stories, Churchill emphasized, were true.

I skipped to the biographical index at the back – anything to avoid the hard work of the inside pages in the blazing sunlight. I recognized some of the names from my wintertime research:

Arnaud, to whom the book was dedicated – captured in 1944, then executed.

Julien (Captain I Newman) – captured and executed.

Louis of Antibes – did I recognize this name? Or was it just the “Antibes” that jumped off the page at me? – He was captured and died on an evacuation march from a concentration camp.

Matthieu (Captain Edward Zeff) – captured and survived.

Taylor, Lt-Cdr “Buck” – commanded his own submarine. Survived.

Vigerie, Baron d’Astier de la – never captured.

These characters were part of the story I’d read several months ago, across a wide ocean, at a time when the temperatures had lingered well below the freezing mark. The story had read like a thriller – except this one had been real.

I remembered the big picture. A British submarine, the H.M.S. Unbroken, had driven into the Baie de la Salis – the very bay beneath me – one night in April 1942. In charge of the operation was the author of this book, Peter Churchill, a member of the British Special Operations Executive. He rowed ashore in the pitch night, sometime around 3 a.m., and mounted the steps that led up to l’Ilette peninsula – landing here, right here, on the ground beneath my bench.

If someone had lingered on the terraces of our Bellevue that night, I’d thought when I first read the story, they could’ve witnessed the landing in the movement of shadows.

Churchill’s mission was to deliver two radio sets and two radio operators (Matthieu and Julien) to the home of Dr Elie Lévy, a kingpin of Antibes’ Résistance movement who lived three blocks up on Avenue Foch. Under the cover of night, Churchill first navigated the streets alone, locating Dr Lévy’s house before returning for his colleagues and supplies. At one later point in his clandestine sweep into Antibes – already scared of the shadows – the British secret agent ran into Dr Lévy himself on the tip of l’Ilette peninsula. What’s more, Dr Lévy had brought with him a man who turned out to be Baron d’Astier de la Vigerie, making a last-minute addition of this diplomat to Churchill’s passenger roster as the submarine departed the bay beneath Bellevue.

That was the story within Duel of Wits that I wanted to read in English, right then, right there on the cement bench at the tip of l’Ilette peninsula, under the burning sun. I heard a couple people approach from behind, stopping to admire the view rather than to pay homage to some timeworn war memorial. A fully formed drop of sweat ran down my right calf and deposited itself on my ankle. Skimming would be the only way. I flipped to the middle of the book and hunched over its musty, yellowed pages. A breeze kicked up. Instant air-conditioning. I was doing the right thing.

Some would say I’ve been behaving a bit oddly all summer. Put one way, I’ve been riding my bike around town with one eye on the road and the other scouring the second-floor facades of buildings where plaques might appear. And if it’s not buildings, I’ve looking at the road signs with more than the necessary curiosity.

I’m sure I’ve looked like a swot. Maybe I am one, as I could’ve been lying on the beach all summer instead. Friends, more kindly, have started calling me a history-buff. Really? History has never, ever been my thing. It was always a jumble of dates and wars and useless information, so I thought – except when my own, paternal grandmother told me stories about the wagon train that went from Pennsylvania to Iowa, carrying our ancestors with it, along with the gold pocket watch that I knew from her display case in the living room and the needlepoint tapestry that hung over her couch.

History was only interesting to me when there was a real story behind it. History was interesting only when it was living.

So that’s what I’ve been recreating over the past year – a living history of Antibes centered around the man, Edouard Muterse, who built our Bellevue all those years ago. Having lived through the destruction of Antibes’ rampart walls, and then the giddy, star-studded rise of Juan-les-Pins, and finally the descent of World War II onto his doorstep, Edouard Muterse has led me through interesting times, to put it mildly.

Midwinter in Toronto, sharing a bowl of steaming latte one morning with my friend Jenny, I tried to summarise what I was working on with my writing project. She’d asked. She listened courteously, seemingly interested, to what was more an essay than a summary. At the end of my speech, she said quite simply, “This project will change you.”

Such a simple but profound statement – and Jenny’s a mere 30-something! When I told Philippe about her comment later that evening, he said, “That’s why she’s the vicar.” Okay, he had a point.

But this work was big and meaningful – to me, at least. And at the end of it all, even if the details interested no one but me, I figured that all this reading of erudite French would at least give my second language a bit of a boost.

So the first thing I did on returning to Antibes this summer was check out that old war monument on the l’Ilette peninsula – the stone I’d glanced at once in the six years we’d been coming here. It had something to do with the heroes of some war, I’d recalled, without having taken in a smidgeon of the detail. Such a distanced stance to war memorials, I believe, is more common among North Americans than Europeans. We’ve never lived through the terrors of a World War on our doorstep.

That June day, a few people had occupied the end of l’Ilette peninsula as I approached on my bike, but I soon realized they were simply admiring the view of Old Antibes. They had no interest in the shard of stone and its green plaque.

But I stopped to read. It was true! The monument did – it really did – place the adventure of the H.M.S. Unbroken in these waters that lapped against the shores of our Bellevue! To express my true joy – after all the wintertime research – that this thrilling mission was in some way linked to the story of our home would’ve made me a freak. So I bottled it and took a picture instead.

Next thing, I rode up Avenue Foch, the trunk road out of Antibes that I’d driven and ridden and walked more than a hundred times before. I headed to the third corner on the right, as Peter Churchill had so carefully identified in his book. Would I really find Dr Elie Lévy’s house, a covert headquarters of the Résistance?

Among the modern condo blocks that lined Avenue Foch were two older buildings with signs posted to their exterior walls: Mr Lefebvre, architecte, Antibes, 1933. Churchill and his mates would’ve walked right past them, I thought. And then there, at the corner of the third block, mounted on the façade above what’s now an interior design and lighting shop, was a marble plaque: Here lived Dr. Elie Victor Amedee Lévy, Captain; arrested May 4, 1942; died in deportation to Auschwitz; hero and martyr of the Résistance; died for France.

The story was real.

Shortly thereafter, I hopped on my bike again to check out 10, Boulevard du Cap. During the war this address was a place to avoid – a hotbed of the Résistance, rented out by one André Girard, even if people didn’t generally know his name.

There was no number 10 mounted along Boulevard du Cap. And there was hardly a commemorative plaque. But I’m sure I found that infamous block of apartments as it was the only building between numbers 8 and 12. Interestingly though completely disconnectedly, the building is situated at the corner of Avenue du Bosquet. A center of Antibes’ wartime Résistance had been positioned just over the fence from the villa named Le Bosquet, the home of Edouard Muterse, the man who built Bellevue.

I want to take a photo of the place, but I hesitated. Just up the walkway there was a wooden balcony with draped rope railings. Two sinewy guys with long hair were lazing up there, having a smoke. It was exactly as I’d pictured Mr Girard with his own buddies, planning their next move.

All summer long, Antibes has been revealing herself to me on these two levels, present and past. This latter level is deeper from the surface, but it’s there, only appearing to those who look for it – and know to look for it.

At Antibes’ bus station at the edge of Old Town, Avenue du 24 Août commemorates Antibes’ libération from the occupying forces in 1944. The road – at least from what I’ve read – seems to trace the path of the US soldiers as they approached from Cannes that day. What’s more, Avenue du 24 Août leads directly into Café Pimm’s, the exact spot where (under a different name) the Résistance had congregated in wartime. That morning, 68 years ago almost to this day, a band of armed résistants had marched from that café up Old Town’s central artery, Rue de la République, singing La Marseillaise. It was the day of Libération. They would’ve passed through the plaza that’s now called Place des Martyrs (the one I’ve always referred to – almost blasphemously now – as Place du Carrousel for the merry-go-round that typically occupies our attention), all the way to la mairie, where they demanded – and received – their hand at the local government.

My stitching together of these facts admittedly could be a bit dodgy – I’m hardly writing a doctoral thesis here – but from all my wintertime reading, I’m sure that most of the story is correct.

Over in neighbouring Juan-les-Pins, Boulevard Edouard Baudoin remembers the man who made the place a famous party town back in the 1920s and 30s. Aptly, the boulevard links the town’s casino with the Hôtel Provençal, party headquarters back in its heyday.

On the Cap d’Antibes, Avenue Aimé Bourreau, named for Antibes’ own hyperactive mayor from the 1930s, intersects Avenue Guide, which carries the name of the family who held much of the land on the Cap on which the mayor built.

The Guides, incidentally, were the ancestors of Edouard Muterse, Bellevue’s originator. There’s a whole section of Antibes that contains streets linked to his history – Chemin de St-Jean, Avenue Reibaud, Passage Cauvi and, of course, Avenue Muterse. There’s another area of town – just around the corner from the apartment rented out to the résistant André Girard – that’s all about this notable family, too, where you find Avenue du Bosquet and Chemin de Guérande. But to explain all these nuances and connections would make me a real bore.

And one day this summer when I managed to peel my eyes from all the plaques and street signs, I found bunkers from World War II – and earlier – on the shores of the glamourous Cap d’Antibes. I simply had to know where to look for them.

It should be said that sometimes all these signs can lead you astray, like this one on a disused door under an arch in Old Town Antibes: Watch out! Trapped local.

I’ll stop. These “discoveries” might be interesting only to me. Or perhaps it’s the route of discovery – that “ah-ha!” moment – that makes the connections so intriguing. What I mustn’t become is a history drone when unsuspecting friends show a whiff of interest.

As I read on the bench at the tip of l’Ilette peninsula, the mustiness of the yellowed pages filtered into the sea air. The breeze united with my sweat to form a glorious, personal air-conditioning. I still considered the umbrellas and drinks at the Royal Beach restaurant below, but soon I sank into this realm of 70 years past. Yes, as I read the events anew in English, I confirmed that I’d understood the story the first time in French.

But, though the big picture had remained clear, I’d forgotten the detail. It was hardly a matter of language; the truth is, I’d simply forgotten. Like the fact that on that dark night in April 1942, two bicycles had popped up in the street out of nowhere. Policemen doing their rounds. Churchill and his colleagues Mattheu and Julien had hidden automatically.

And while I remembered Churchill’s encounter on the peninsula with Dr Lévy, I’d forgotten the tangential way in which it began. That night, as the small group huddled in the darkness of their clandestine mission, Lévy launched a question for Churchill – before he even bothered to introduce the diplomat who loitered alongside them. Where, the doctor wondered, were the faked baptismal certificates for his two daughters? Churchill had promised the papers so that Lévy, a Jew, could avoid having his house (purchased in his daughters’ names) confiscated by the Germans.

I’d forgotten, too, that this expedition helped Churchill get a promotion. But I did remember all these details now, as I read them again in the blazing sun.

There was a new tidbit that I pulled from the English text, too, quite probably because the Musée de la Resistance’s website had omitted the detail altogether. The success of this particular mission had rested on fundamental knowledge that Churchill had amassed in his earlier years. It was then that he’d lain on Antibes’ sandy beaches. His parents, the British secret agent reflected, had unwittingly financed this segment of his career.

I wondered anew, given our family’s consecutive summers in Antibes, what we were launching in our own seven-year old’s journey.

By then I was officially boiling. My face burned and my water bottle was almost dry. I’d read more later, I told myself – and elsewhere, in conditions where I could actually absorb the information. I hopped on my bike and headed back toward the road – but my retreat was too hasty. Having just sped by the stone monument to the H.M.S. Unbroken’s expedition, I circled back to re-read the green plaque. It was written in both English and French, but as is the case with so many translations, the two halves gave different information.

The monument remembered the landing of the H.M.S. Unbroken submarine, under Captain Peter Churchill, on April 21, 1942 – and commemorated all those who took part in such landing operations.

It was presented to Major Camille Rayon (a major Résistance player back in the day) by Lieutenant-Commander C.W. Buck Taylor (who drove the submarine that night) on May 23, 1992.

The last line then caught my eye. It spanned the centerline of the plaque, occupying both the English and French sides, and actually protruded from the face of the stone:

En hommage au Docteur ELIE LEVY (LOUIS)

qui dirigea cette operation, et mourut en Déportation

In tribute to Dr Elie Lévy, code name Louis, who directed this operation and died in deportation.

I had learned the story of the H.M.S. Unbroken through the eyes of Peter Churchill, a British secret service agent. But local history – the collective memory of the people who live here in Antibes– comes through a different lens. To them, the mission was directed by Dr Elie Lévy, an Antibois. He was one of their own. To them, it was Lévy who was the heart of the mission, not Churchill.

History buff or not (and I’ll argue not), I’ll never really get French history. We write our own texts, from the perspectives we know. Still the alternative angles are worthwhile. It is precisely the stories and different voices that keep history alive.

There’s a whole other world here in the Côte d’Azur. It lives invisibly alongside the sandy beaches and sunny cafés. And it’s breathing, shallowly, for those who stop and linger.