I don’t want to go anywhere. I just want to spend a week in my bed.

This from Lolo, my ebullient nine-year old. Who knew summer could be so exhausting.

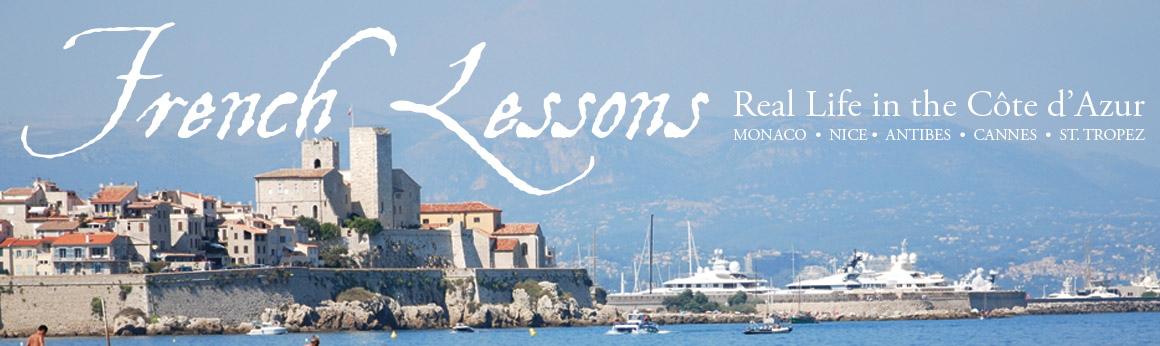

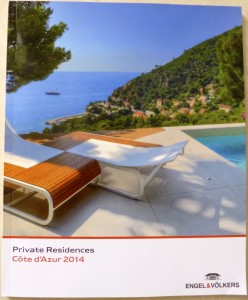

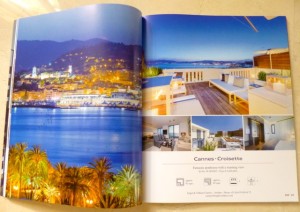

As French Lessons wraps up for the summer of 2014, we admit that life in the Côte d’Azur can be a bit strenuous – mostly in a good way, of course. And we’ve done our best to share some of the more interesting stories along the way.

Most recently we’ve reflected on the past, harnessing the world’s rightful absorption in World War II commemorations. Our take was a compilation of research and personal memories around the precious commodity of food, preceded by the local recollections of an astonishingly vibrant 100-year old.

We’ve certainly looked at us-versus-them topics, trying to distill once again what makes France so appealing and so frustrating at the same time. If it’s not the hoity-toity pharmacies, it’s the tax-laden economy. Or perhaps it’s the country’s live-and-let-live service mentality.

We’ve also dished out the diamonds, touring one of the Cap d’Antibes’ storied mega-properties and getting up close and a little personal with Monaco’s Prince Albert II. We’ve even taken a stab at celebrating America from the heights of the five-star Grand Hôtel du Cap Ferrat.

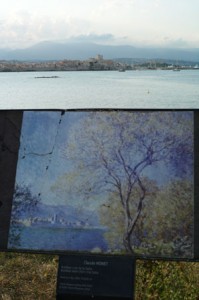

Or we’ve simply sat back and allowed pictures to tell the story, first of the Côte d’Azur’s more mellow, pre-summer season and then, perhaps a bit too quaintly, of our love for Antibes, our summer hometown.

Through these celebrations and small heartaches, we realize 2014 was a summer like no other. For one, we had a bumper fig crop from our glorious figuier. It’s amazing what you can do with a little ingenuity – and a new golf ball catcher.

More importantly, the influx seemed more modest this year in Antibes and neighbouring Juan-les-Pins. We don’t have hard stats, but you could feel a relative calm – certainly through the end of July, anyway. There were days when you could actually park a car in town without needing to be utterly and terribly creative. Locals fed us anecdotes about restaurants and businesses; outside those serving the very high end, figures were down around 20% at the end of July. Juan-les-Pins’ big casino saw a drop of more than 30% in the same month. One friend called this summer Juan-les-Pins’ worst in ten years and predicted a lot of storefront changes in 2015. Frankly, for all of us folks who simply stroll the streets this jam-packed corner of the world, the results were a bit cheerful – but we do share our sympathies with the friendly commerçants.

Could it have been the weather? On a “date night” in early July, Philippe and I headed to Plage Les Pêcheurs, a beach restaurant in Juan-les-Pins. Fortunately we chose the table under the awning. Passersby on the beach brushed off the night’s earliest sprinkles and turned inland and gawk at the fireworks in the mountains. That night’s storm tallied 206 lightening strikes in the Alpes-Maritimes departément. Two weeks later – all too shortly after Lolo came indoors from her inaugural windsurfing lesson – an afternoon storm logged an impressive 377 strikes in our region – in just two hours’ time.

All this grandeur in a land that sees only drops of rainfall during the typical July! The forecasts may have kept the juilletistes, as July vacationers are fondly called, at bay. (This month, at least in Antibes, the aoûtiens seem to have outranked the juilletistes, finally pushing our poor nine-year old over the top and under her bed sheets.)

But there’s a deeper, more ominous difference in this summer’s season, too. More friends talk about leaving. They’re talking about really leaving. No longer are their words the whimsical, rosé-enhanced dreams that you have about greener pastures. French people are worried about their futures. Taxes, regulations and a major distaste for the federal government have sapped the national work ethic, and the economy fast approaches a downward spiral. (The French statistics agency puts a more positive spin on everything, describing this summer’s second quarter of consecutive zero growth as “holding steady”.) Sadly for the country, the next wave to leave could very well be its small business owners and entrepreneurs – the ones who have so far kept the economic gears greased.

The summer of 2014 certainly has been outside the norm. But a few steady themes run through our summers, too. Yes, we’ve had lots of visitors again this year. Yes, we’ve dealt with pests – the geckos as usual, but instead of an enormous garden snake this summer we’ve enjoyed a young headful of des poux. Lice. Apparently there was an epidemic.

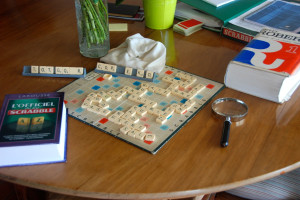

Yes, too, to spending an evening or two across the road chez the hard-partying Hauptmanns. One dinner for eight around their terrace table included an erudite gay couple and a former UK Attorney General, so I guess we made a decent quorum. Lubricated by the fruits of the Hauptmann’s prolific family vineyards, we chatted in English, French, German, Russian, Norwegian and Hebrew until the wee hours, deciding at last that our host country is both wonderful and unsustainable.

This summer we’ve also maintained a couple rather intriguing themes related to our Bellevue. For one, someone again – out of the blue – wanted to buy the grande dame by the sea. Angela, our impassioned estate agent, rang one afternoon in early August. Just checking, she asked, but could your house be à vendre?

Non, I said, stunned – but then couldn’t help find out the detail. A Frenchmen tracked Angela down through the neighbouring port. She thinks he represents a Russian family; they love Bellevue from the outside.

With French taxes being as they are (and considering what they still could become), you wonder who is sanely thinking about buying anything around here these days – unless, of course, the Russians experienced a giddy, at-first-glance coup de cœur with Bellevue, just as we did nearly a decade ago.

Again this summer, too, we’ve broadened Bellevue’s own story.

Marie, our fiery English personal trainer friend, always has the local scoop. Visiting Bellevue one lunchtime a couple weeks back, she gazed out from our terrace into a bay full of megayachts.

The people staying on Tatoosh are lovely, she told us. She’d just been whisked out to Paul Allen’s 303-foot yacht for a couple sessions – and a leisurely lunch to boot.

Marie’s gaze passed onto the navy-hulled, 377-foot Luna, formerly part of Roman Abramovich’s personal fleet – this one of his yachts having an extended “beach” platform at the stern. Madonna was onboard last week, Marie said as nonchalantly as she could knowing full-well that the gossip was juicy. Our personal trainer friend paused only briefly for effect. Apparently Luna has pap shields, she continued.

“Pap”, she had to explain for us, was short for “paparazzi”. The special shields somehow blocked photographers’ over-eager lenses.

Megayachts, Madonna and pap shields – time with Marie is always a treat – but the next bit of news interested me even more. A few days later I visited her in her old-town studios.

I have a gift for you for lunch the other day, she said quite simply. I’ve found someone who used to live in your house.

That same afternoon Philippe, Lolo and I invited Geneviève and her children to visit Bellevue. They were leaving their summer townhouse in Antibes’ old town the next morning to return to Switzerland. School started imminently. It was now or – well, a while from now.

Ça me dit quelque chose, the willowy blonde said as she peered out over our terrace into the bay below. Her language floated between French and English. The view told her something. She remembered Bellevue from long ago, but she knew our grande dame by her former name of Lou Gargali.

Geneviève’s visions were more snapshots than rolling video. She was very young, only three or four years old, when her grandparents rented Lou Gargali for the summers. It was the late 1960s and early 1970s. This woman, I realized, was my peer. She and I were in the process of forming our earliest childhood memories at the same point in time. While she lingered here in Antibes on our balcony, soaking up the seaside view from Bellevue’s sturdy frame, I stood on the other side of the Atlantic looking out over the bow of a houseboat, the wind streaming through my long, curly hair as my family cruised the meandering Mississippi.

Suddenly the soul of Bellevue – or Lou Gargali, as she was – seemed more durable than ever. She has witnessed much in her years – we already know that, having found several of her earlier occupants like Arlette Aussel, who lived here as a girl in the early 1940s; Jean-Claude Logut, whose childhood ran here through the later 40s and early 50s; and Michel, who often vacationed here as a teen with the Everard family in the 60s. But Geneviève was the little girl who occupied Bellevue when I, too, was a little girl. Somehow her memories on this terrace added personal depth perception to my understanding of our dear old Bellevue.

Geneviève’s initial recollection of life within Lou Gargali’s walls was her humidité. Humidity was the reason that her grandmother had insisted on changing this seaside property rental to another home just down the coastline. Geneviève remembered a dock outside Lou Gargali (a feature that would’ve been forbidden as French laws had recently banned private constructions at the shoreline – but as ever, there must’ve been some flexibility in the law’s implementation). She and her family fished a lot, right outside our home and along the length of the beach. The catch was bountiful. They hooked grey mullet, grey-and-pink fish pronounced zheer-AY, and beautiful round, silvery fish with spiky tails pronounced sart. There were moraines, too, and octopuses, starfish, crabs, tomates de mer (literally “sea tomatoes”, or common sea anemones), and sea urchins. The kids even chased hermit crabs.

Ça me dit quelque chose, she said. She summoned the same phrase while standing at the base of Bellevue’s wide circular staircase that unites the floors. Geneviève knew this place. She remembered, too, the image of a fountain that once occupied the gardens. No matter the decade or the age of the beholder, we are sure of one thing: Bellevue makes a lasting impression.

So again this summer, thanks to the good fortune of our longevity and connections within this community, we wring out a few more visions from Bellevue’s past. It makes me wonder who might queue behind me at the boulangerie up the road, or who might sit beside me at a sidewalk café in the old town while I sip an intense, foam-dolloped noisette? What story might this person share if only I asked the right question?

These daydreams must wait for next summer. As Lolo beds down under her warmer blankets, Philippe is ready to go back to work in Toronto. He says that he needs a rest.

Me? I’m not ready to leave our corner of France. I don’t think I ever am. There’s this marvelous, never-ending stream of stories that seems to wash up on Bellevue’s doorstep every summer, week after week, unannounced.

Which is exactly why we look forward to welcoming you to French Lessons once again next year.

Parking has always been a problem in Monaco. Signs like this one dot the principality’s roads, telling drivers not only where to park – but how many spots are left, too.

Parking has always been a problem in Monaco. Signs like this one dot the principality’s roads, telling drivers not only where to park – but how many spots are left, too. Philippe swerved our car into a narrow spot along this road, and I ran out to take a few shots on my phone. The two truckers stood in a shady spot on the opposite side of the intersection, chuckling – hopefully at my eagerness rather than the sight of me in pilates gear. I flashed them the thumbs up for their perfect ingenuity before popping back into the passenger’s seat.

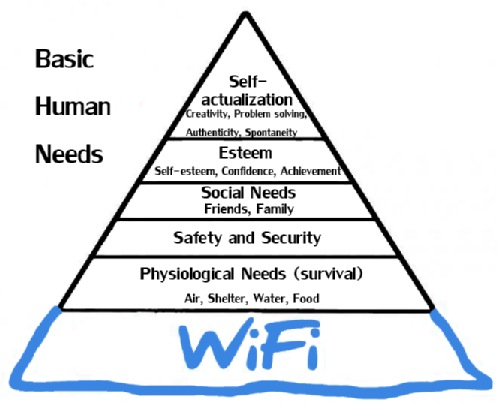

Philippe swerved our car into a narrow spot along this road, and I ran out to take a few shots on my phone. The two truckers stood in a shady spot on the opposite side of the intersection, chuckling – hopefully at my eagerness rather than the sight of me in pilates gear. I flashed them the thumbs up for their perfect ingenuity before popping back into the passenger’s seat. You never realize the depths of your addictions until they’re suddenly out of reach. Fortunately a couple WIFI-friendly cafés opened up recently in Antibes. Three cheers – no, a full-on, Fourth of July fireworks festival! – for

You never realize the depths of your addictions until they’re suddenly out of reach. Fortunately a couple WIFI-friendly cafés opened up recently in Antibes. Three cheers – no, a full-on, Fourth of July fireworks festival! – for  . . . and for

. . . and for  So we are managing quite nicely around the Côte d’Azur’s hiccups. And yet. And yet, there’s something far more fundamental – some je ne sais quoi – that keeps us coming back here, year after year, for more . . .

So we are managing quite nicely around the Côte d’Azur’s hiccups. And yet. And yet, there’s something far more fundamental – some je ne sais quoi – that keeps us coming back here, year after year, for more . . . Let the season begin!

Let the season begin!