Philippe ran into our friend Jean-Louis in the old town of Antibes a couple days ago. Jean-Louis, a well-connected Frenchman, was glad to see my husband again. He was a bit relieved, too.

I thought you might not be back this summer, the Frenchman said.

Indeed, Philippe explained, we almost weren’t. The truth – the obvious but unspoken words exchanged between these two friends – is that our family was nearly Holl-ended.

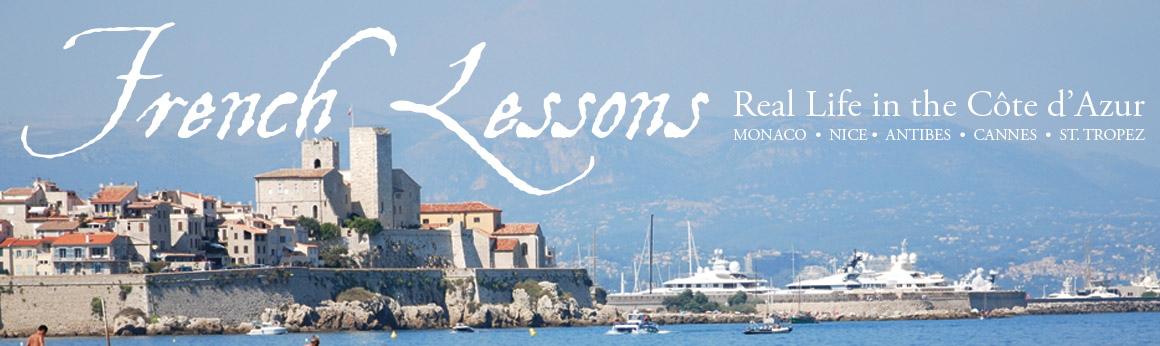

It started in Toronto on a soggy day in December – Tuesday, December 10, to be precise, as each day would begin to matter. A registered envelope arrived at our front door with news from France: The value of our cherished Bellevue – the ruin on Antibes’ Côte d’Azur seaside that we’ve lovingly resurrected over the last seven-odd years – had skyrocketed. It had, in fact, tripled!

Pop the corks, you’d say! Tripling the value of your home is a massive windfall! We were suddenly the implausible, grinning Grand Prize Winners in one of those Sweepstakes Clearinghouse letters.

Except that there was no note of congratulations anywhere within the registered French envelope. Quite to the contrary, the only winners in this game were its senders. Our sudden windfall simply served to generate more tax.

We’ve all heard about French actors and singers, athletes and businessmen who’ve been what I call “Holl-ended”. The famous tax hikes of France’s new Socialist Président Hollande have prompted some of the country’s most celebrated names to flee. Only three days before that registered letter arrived in Toronto, for example, the famed French actor Gérard Depardieu became a Belgian tax resident in order to escape the new French levies. France’s Prime Minister called the actor’s calculated departure “minable” (pathetic).

A lot less famously, we Canadian-Americans who own Bellevue were getting hit by the country’s other notorious tax: the impôt de solidarité sur la fortune, or the ISF. France is unusual in the way it levies this annual wealth tax on all French assets above a certain threshold – and what luck! Ours had just blossomed magnificently. We’d become the latest targets in Mr Hollande’s grand attempt to chase taxpayers out of the country.

It is bad manners in France, I know, to discuss all matters of finance, so I’ll pass over the detail. But I forge ahead because the story is, at the least, instructive in the French art of flexibilité.

We had 30 days to reply to the French Government’s letter. This period conveniently spanned seven days of Hanukkah, Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, Kwanzaa, Boxing Day, New Year’s Eve, New Year’s Day and Epiphany – not to mention Human Rights Day, which fell curiously on the day we received the winning letter. These holidays, and the weeks connecting them, were all perfectly good reasons for anyone who could possibly help us, to not be in the office.

If, after these fixed 30 days, the government received no response from us, Bellevue’s new valuation stood. Our tax payment – what we’d owe the government each year – would go up to something like the price of a typical American home.

Philippe vowed to sell Bellevue. I pleaded that we find help, preferably from someone who didn’t observe Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa or the New Year. Our holidays passed on the western side of the Atlantic with a decent bit of unspoken angst, at least on my part.

Three days into the new year, actor Gérard Depardieu returned to the headlines. He became a Russian citizen. The sub-headlines mentioned the beauty of Russia’s 13% flat tax.

The very next day, with our 30-day response deadline looming, there was an email from our newfound savior, Jean-G.

Having secured a 30-day extension from the government, our new French tax accountant outlined the next steps. He was busily amassing details of comparable house sales, thanks to a study he commissioned by a certified appraiser with a double-barreled surname. Her credentials were amazing, as was the hyphen. What’s more, she was – how shall we say? –personally connected to all the right people.

Jean-G outlined the process. We’d debate Bellevue’s valuation with the administration, heading up the ranks as need be. If we still weren’t satisfied at the top, we’d hire a lawyer and take the issue to court.

Thanks to our new tax accountant’s instruction, we were expecting the next registered envelope that arrived in Toronto. On February 20, we learned that Mr Hollande’s team was revising our taxes retrospectively. Bellevue’s extravagant new valuation would apply not just for 2011, but for 2010 and 2009, too. Again, there was no trace of confetti.

Three days later Gérard Depardieu became an official Russian resident, thereby establishing a new way to escape France’s hefty taxes. The actor’s new permanent address? 1 Democracy Street.

Meanwhile Jean-G beavered away, negotiating our way up the chain of administrative command. He tested every avenue for the best result, including the possibility (which he went on to prove) that the government had overestimated Bellevue’s floor space – and therefore our tax base – by more than 50 square meters. All the while, our case escalated.

One day, Philippe was talking business on the phone with his buddy Matthieu, a banker in Paris. My husband mentioned our ordeal. Soon, he said, he was coming to Matthieu’s native land to meet with the Directeur Général of the Côte d’Azur’s ISF bureaucracy. This guy was basically the top dog before we brought our case before a judge.

The Parisian banker gave it to Philippe straight. We had only one hope in succeeding, he said. Philippe had to lay on his Quebecois accent good and thick.

Matthieu’s tactic had to be right. That long-lost-cousin trick already has come in handy in countless important negotiations here in the south of France – like when we’d forged an agreement with the city’s garbage collectors to start picking up our trash.

And then the big day arrived. On April 2, at 2:00 p.m. precisely, the industrious Jean-G swung into the administrative commission in Nice. His hair was disheveled, as if he’d never found time to comb it; his stocky body was pumped, fidgety even. In his hand was a thick portfolio of research, and at Jean-G’s side was the full-throttle Quebecker Philippe. The two men took seats in the Directeur Général’s office, a utilitarian space surrounded by neat rows of dossiers packed into towering bookshelves.

They presented Bellevue’s case to the skeletal, regional head of the ISF. There were concrete facts. There were interpolated figures. There was discussion. There were shrugs. There were concessions. There was more discussion. There were more shrugs. Finally, when the gap between the government and private valuations seemed irreconcilable, Jean-G submitted the ample dossier of valuation research collected by our certified appraiser with the fancy surname and connections.

The Directeur Général, a quintessential, eagle-nosed French bureaucrat, noted the author of the weighty report. Ah, Madame Double-Barrel, he said. Just show me the final figure.

At last, two exhaustive hours later, the meeting produced a result. Philippe emailed me over the Atlantic, were I was busily pouncing on my Mail icon at the sign of any new message.

“I’m happy with the result…” were his opening words.

I was breathless. I was relieved. I had a little party in my desk chair in Toronto. Basically put, if we started at 1 and they started at 10, we ended up around 3. This still represented a 50% increase in our annual tax charge, mind you, but it was a number we could at least live with.

The adjustments made in Nice that day were hardly won by the discovery of loopholes in France’s well-thumbed laws. No, they were delivered through effort, strategy and an appreciation of that subtle notion of French flexibilité – the same fluidity in life we confronted when negotiating Bellevue’s garbage pick-up.

Christelle, our favourite Antibes taxi driver with the outrageous spiked heels, drove Philippe back to the Côte d’Azur airport that day in early April. Talking to Christelle in her taxi is always like gossiping with your hairdresser. The discussions somehow fall outside the usual French maxims, such as the one about not discussing money. Quite probably this is because for much of the day, Christelle drives around foreigners – often the wealthy, new compatriots of the “pathetic” Mr Depardieu.

Cruising the Côte d’Azur highway to the airport, Philippe told Christelle about our ISF dramas. He told her the backstory and explained the hard-fought negotiations leading up to that April day. Finally he shared the reduced valuation that he and Jean-G and the team had just achieved for our cherished Bellevue.

That’s it?! Christelle was astounded at the final number.

Philippe agreed. Christelle was right. Angela, our long-time estate agent, also had valued our property a smidgeon higher than this end result.

No, Christelle insisted. That’s hardly what she meant. Her clients constantly beg her to let them know – a-s-a-p – if a seaside property should come up for sale in the Côte d’Azur. Christelle-the-Taxi-Driver vowed she could sell Bellevue tomorrow! And for a much higher price!

One thought on “Saving Bellevue: The Skyrocketing French Wealth Tax”