Tania Laveder had hoped to write her own story, but over the years she has lost some of her Russian. She learned German only for the purposes of survival. The Italian of her in-laws remains fairly non-existent. And the French that has governed her life for almost 70 years now – well, she never approached the language with the sincerity of a student. She was always busy raising children. If she had tried to write her story, she feared no one would take it seriously.

May I write your story for you? I ask Tania. In English?

Cent pour cent! she says, her hands and arms waving enthusiastically in the close space of her bungalow on the Cap d’Antibes. 100%! You can do what you want with it!

This post is a best effort. I’ve tried to understand, synthesize and tell Tania’s story with both accuracy and simplicity. The way this 93-year old shared them, the events tumbled out backward. Her memory is clear – often too clear, she thinks – and each vision she recounted seemed to unlock an earlier one. The pieces slid around like a puzzle and then locked into place. Gradually we worked our way through the lands of four countries that were centrally involved in World War II.

I couldn’t offer this post to readers without Philippe. He was at my side during all conversations with Tania, joining us on hard-backed chairs around a table in a sitting room that opened directly off the narrow lane. Philippe led our conversations; I only fed him ideas of what I hoped to learn. While Tania and I both speak French, we’d struggle to understand each other with our accents. Still, she included me in her responses with her strikingly clear, blue eyes. I also must mention our friends Mirka and Marie. Their help was essential in arranging meetings with this long-time resident of the Cap d’Antibes.

As towns along the Côte d’Azur celebrate the 70th anniversary of Libération this week, French Lessons is privileged to share the story of this woman having astounding vitality, an acute memory and important stories to tell.

Cossack Roots

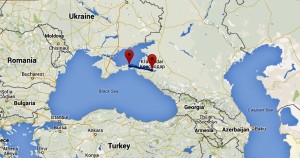

Tania Laveder grew up in Cossack country, just north of the Black Sea, in a village made up of farmhouses dotted among sprawling farmlands. Her father was a veterinarian, an occupation that was useful and necessary in the region. His work would keep him safe through the coming devastation.

Twenty-five hundred kilometers away from these Soviet pastures (as a crow flies), an Italian couple raised a family here in the Côte d’Azur – high on the Cap d’Antibes, to be precise, on a narrow, dead-end street called Chemin des Mougins. One son – the one who matters in this account – was only six months old when they arrived. They were new immigrants, part of a large Italian community within a town near to the Italian border.

When Tania was 18, she enrolled in medical school. She was sent 50 kilometers from her Cossack village to the regional capital of Krasnodar. She left behind her parents, three brothers and a five-year-old kid sister. It was 1941.

The following springtime Tania received a letter saying she must report home the next day. Tania dutifully took a train back to her village, but no one was there. Her house was closed. She tried the neighbours, but they were gone, too, as were all the animals. Everyone – every living creature – had been evacuated. They’d fled to the mountains.

The farming country of Tania’s homeland lay between the Black and Caspian Seas. The area was rich with oil, a commodity needed desperately by the Germans. The Russian military evacuated their countrymen because they were given orders to blow up their own rigs.

Tania’s family had left without saying goodbye. She also realized she hadn’t eaten in two days. She decided to walk to the main street, Krasniput (spelling uncertain).

You’ll like this, Tania says. She’s a vital and hearty woman with fine, white-blond hair pulled into a neat ponytail. The name of the street means – she searches for a French translation – Rue Rouge. Red Street. Her wide cheekbones spread as she chuckles at the incongruity of it all.

Someone was waiting for her at the mairie. A medical student had useful skills. She received mobilization papers. She was headed to la première ligne. The front line. It was May 1, 1942.

Kerch Nightmare

Two hundred kilometers west of Krasnodar, on the easternmost tip of the Crimean Peninsula, Kerch was burning. The Germans had mounted a massive bid to expel the Red Army. The Russians mobilized thousands of women to help their injured soldiers. First Tania had to cut her hair. Then she boarded a bus. She’d never travelled; she always had been studying. When the group reached the Black Sea, they waited three days for a ferry crossing to Kerch. The sea was trop minée. They could see the mines floating in the strait.

When Tania reached Kerch, she found bodies everywhere. A mere first-year medical student, she arrived alongside des vrais médecins et chirurgiens – qualified doctors and surgeons – but she knew no one. The Red Army continued to fight, but there was almost no one left. In the night Tania could see a distant fire. She could hear guns and cannons.

I found a copain de mon père, she says. My father’s friend wondered what I was doing there. Why wasn’t I at my studies?

It sounds as though this family friend wanted to take Tania back home, but no one was giving orders. The Russian leaders were dead, and the remaining officers lacked training. No one knew what to do.

Je mélange tout parce que c’est trop long! Tania says, her voice suddenly tired. I mix everything because it’s too long!

Given the reverse chronological sequencing of her recollections, we’ve been at it for an hour and a half at this point. It’s a testament to the clarity of the discrete scenes running through Tania’s memory. Stringing them together is her main complication, but one thing is sure. She wants to talk. She wants to tell her story.

C’était une aventure! Philippe says, trying to add some levity.

C’est trop d’aventure! It’s too much adventure! Trop! If I were younger, I’d write a book.

Eventually the Red Army fled Kerch. Tania and the others were left to their own devices.

I’d never held a gun in my hand, she says. I had to experiment. She also recalls standing between two women when a bomb came down. As the incident rolls through her mind, she holds out her hands at either side. Tania took the hands of both women. She glances at her left hand and shakes it. The woman on her left was about 40 years old, a vrai médecin. The doctor ordered them to jump into a hole, itself a crater left by a recent explosion.

La médecin m’a sauvé la vie, she says. The doctor saved my life.

Another bomb dropped and exploded. Tania’s ears bled. She was in a state of shock. Rather than feeling fear, everything became surreal. Of the 2,000 mobilised Russians who surrounded Tania prior to this bombardment, she was among the 56 who survived.

Tania’s walk along this narrow line of life and death will become a frighteningly recurring theme in her coming years.

The survivors found refuge in nearby catacombs. Tania’s not sure how long she hid there. Three or four days maybe?

Je mélange tous ici, she says again. Her memory gets muddled. She’s clearer for Philippe and me on a follow-up visit.

The Germans were at the gate of the catacombs with machine guns. If Tania and the other survivors didn’t come out immediately, they threatened gas. Tania was only 19, and she was scared. She and her compatriots came out of the tunnels with their arms up. She was wearing a Russian military outfit but had des pieds nus, bare feet, when the Germans captured her. She adds a side note. Her parents had told her to pack a small dress if ever she was mobilized. They’d advised her to change her clothing if she was in danger of being captured.

Clearly it was too late. The Germans packed the Russian prisoners into trucks. Shortly thereafter they bombed Kerch.

Twenty-five hundred kilometers to the west, France’s Côte d’Azur remained a free zone, but it was becoming a hotbed for the Résistance. Rationing put severe curbs on the food entering each household. In Antibes, tensions rose between the local French and Italian communities. Italy had sided with Germany. The enemy’s border was less than 60 kilometers away.

The family living on Chemin des Mougins, the one that still spoke a rural Italian dialect at home, knew real hunger. The six-month-old son was now a young man. If he didn’t leave the household, his father would. Either way, there’d be one less mouth to share the daily rations.

The young man went to work for a German furniture maker about 50 kilometers south of Hanover. It was wartime, though, so the factory refurbished des cases des munitions – ammunition boxes made of wood with steel reinforcements. The young man wasn’t paid. He simply earned housing and, critically, food. He went to stay alive.

Prisoner Life

Tania managed to slip away from the prison truck. She was still barefoot. A farmer put her to work, but soon another truck came by and spotted a Russian working in the fields. She was put on a train.

It was hardly a train de voyage, Tania says, wagging a gnarled index finger. It was a train bestial. A cattle train.

Tania became one of 2,000 prisoners at a work camp about 50 kilometers south of Hanover. In the mornings the guards gave her a cup of hot water and half a piece of “bread” made from equal parts flour and sawdust. For lunch there were industrial-sized milk cans filled with soup that Tania scooped out in a cup. Sometimes her food came from une grosse casserole, a big saucepan.

The food was dégoûtante, she says. Revolting. The soup tasted like dirt. When the factory owner fed his two pigs with the prisoners’ food, the pigs wouldn’t eat it.

The prisoners were put to work. For three months Tania was a soudeur, a welder. She demonstrates how she manipulated a welding gun and solder material. She was the only woman who could do the work.

Most of the time, though, she repaired broken ammunition boxes. With her fingers she draws a one-by-two-foot box on the yellow-and-red-poppy plasticized tablecloth between us. She repaired boxes sent back from the front. Broken boxes came up to the second floor of the factory, and they returned fixed to the ground floor. It was the same thing over and over, day after day, year after year. The repetition numbed her.

The factory was very cold inside. Tania was in charge of packing the chaudière with wood chips and starting its fire. One time she did something wrong and the boiler exploded. Cinders blew out and seared her hands and her face. They burned her hair, scalp and eyebrows. Tania touches her left eyebrow. Some of it never grew back.

But the factory owner was good to her. He was un gros-gros Allemand, she says, delighting in sharing this detail. The big-fat German covered her wounds with the right balms and creams. She taps her gnarled finger on the table. He saved me, she says.

While Tania worked at the factory, she lived with Russians, Ukrainians, Belorussians and other young women from all over the Eastern bloc. All 40 of them crammed into a single room filled with bunk beds. A woman sleeping nearby Tania’s bunk caught a malady and died the next day. Tania caught the same bug and her fever soared to 40°C, but she lived.

It was in this situation that Tania, the Russian prisoner, met Pietro. Pietro Santo, she says emphasizing his middle name. Comme Saint. She insists on this precision during our follow-up visit when I ask about writing this story. Her fortitude is disarming.

My friend Mirka, Tania’s neighbour in Chemin des Mougins, will later explain how the couple met: Pietro simply asked Tania if she would do his laundry.

Pietro’s life had improved from the hunger he and his family knew on the Cap d’Antibes. Since he left, the days there only had deteriorated. In late 1942, the Italians invaded. L’Occupation italienne began. Ten months later, in September 1943, the Italians signed an armistice with the Allies. That same day the Germans attacked. Their occupation was even more severe.

Pietro worked at the neighbouring factory to Tania. The owner had noticed the Italian’s hard work and had compensated him with his own accommodations. Tania indicates that this independence was a big deal. Presumably, Philippe and I will reflect, it offered better access to food. Mirka will confirm this notion. Pietro had a good relationship with the local bakery, and he supplied Tania with fresh bread. He saw her every day.

Tania mentions the carrots and potatoes and rutabagas he brought her. There were a lot of rutabagas, she says. But he kept me alive. She squints. Tears fill her eyes. Together they spoke German. The Russian woman and the Italian man had learned a third language in order to survive. In the end, it became their earliest means of communication.

Nascent Freedoms

About six months before the war would end, one of Tania’s Ukrainian co-workers was called to work on a farm belonging to an elderly couple. She herself grew up in a farming family and was relieved by this advantageous posting. Before leaving the work camp, the young Ukrainian woman told her colleagues that she was engaged. Her fiancé had escaped mobilization because he worked his parents’ farm following the death of his brother in the war. The Ukrainian woman already had made herself a wedding dress from scrounged pieces of cloth. She gave Tania her new work address. Tania didn’t know if she’d ever use the information – the Ukrainian was a colleague, not a friend – but you kept these things, Tania says.

The British and Americans were advancing on Berlin, the German capital. Pietro worried that Tania would be repatriated to Russia after the war. He wrote letters to her asking her hand in marriage. Tania didn’t reply. Pietro sought support from a friend who’d moved to Germany from Monaco. The two young men often walked together and stood beneath Tania’s window, calling out for her answer. Finally Tania replied that she didn’t have a wedding dress. Pietro said not to worry; they’d have a simple ceremony. Tania hardly liked that idea, but she said nothing more. Part of her wanted to marry simply because she was afraid she’d have no one left in her life after the war’s devastation.

Tania and Pietro at one point decided to visit her former Ukrainian colleague on the farm. Presumably the motivation was food. After a while, the couple mentioned they were getting married, and Tania worried she had no dress. The Ukrainian offered her wedding dress to Tania. She no longer needed it. Her fiancé had been called into war. He’d just been killed. Tania refused, but the Ukrainian insisted.

Elle a fait la robe elle-même! Tania says. She made it herself! My wedding dress came from someone I only knew from work! Même une Ukrainienne – and I’m Russian!

A few months after her muted acceptance, Tania and Pietro married in a German village. It was a Sunday in the spring of 1945, three weeks before the war ended. The Ukrainian friend attended the ceremony. Tania wore her friend’s handmade dress and then returned it. The Ukrainian didn’t want it back, but this time Tania insisted. Her friend would find someone else. Tania doesn’t know how that story continued.

As the British approached, fear mounted within the German guards. They suspected the prisoners would take revenge following the brutality of the recent years, so the guards disappeared. Tania had been a prisoner of war for three years.

New Start

There was no one looking after the prisoners when the British arrived. What’s more, the Allies didn’t know what to do with these captives following a recently signed agreement with the Soviets. The liberators gave the former prisoners three days of grande liberté. They could do whatever they chose – notably pillaging German homes. Tania and Pietro refused to take part in the free-for-all. They stayed in their room and slept. The German factory owner even offered Tania a gift. For the various sewing jobs she’d done for him, he gave her a suitcase full of haricots blancs. Dried white beans.

The couple was sent to northern Italy, to the town of Montebello Vincentino, where Pietro had an aunt and uncle. They joined a convoy of now-freed prisoners that packed into a train for Italy. Along the way the train derailed. Pietro jumped, and he yelled for Tania to do the same.

Il m’a atrappé au vol! Tania says breathlessly. He caught me in midair!

The Résistance had removed a piece of the rail. A handful of train cars rolled over, killing several passengers. Tania had survived once again.

Tania and Pietro arrived in Montebello Vincentino a couple days later. No one was expecting them. Pietro’s aunt and uncle took them in only because they had a suitcase full of beans.

Tania soon realized she was pregnant. She and Pietro wanted to reach France, and more precisely to join Pietro’s family on the Cap d’Antibes. Tania was heavily pregnant when she and her husband walked 70 kilometers to the French border. Pietro’s parents had paid off a border guard – neither Tania nor their son had any papers – and from there Tania’s in-laws had arranged a black car to take them in the dark night from the French border to Antibes.

J’étais très, très inconfortable, Tania remembers, moving an arm automatically toward her lower back. The pain was agonizing.

Tania had the baby the next day in her in-laws’ home on Chemin des Mougins, the very house she occupies today. It was February 1947. She lost her son a couple weeks before his first birthday.

It was here that Tania began her story for Philippe and me. Despite the bombardments, inedible food and imprisonment, it is here that her sorrow may remain the most intense. The memory of her son makes her cry. She draws a thick handkerchief from her pocket.

As an illegal immigrant, Tania had no right to a doctor. Her in-laws had warned her to talk to no one. Fortunately her son was costaud (strong, sturdy) and intelligent. He drank du lait sucré, sweetened milk, thanks to daily rationing tickets that continued to govern the food supply in Antibes. Then rationing disappeared, and the milk changed to something else, something non sucré. The baby got diarrhea.

Tania sought help despite her legal status. There was a doctor who visited her neighbours on Chemin des Mougins; she had chatted with him on his journeys to see these patients. Her son had been sick for 15 days when the doctor visited. The baby needed penicillin, but this medicine was only available in Paris. The doctor gave her son a shot and then, touching Tania’s shoulder, promised all would be fine.

The injection simply relaxed the baby. His raspy breathing improved in the night as he slept. But when Tania woke the next morning, she found him dead. Her eyes squint again. She cries briefly, then blows her nose.

They buried the baby in a tiny wooden coffin. Tania marks out about two feet on the tablecloth with her hands. At the cemetery she realized something was very wrong. In the same area as they buried her son, she saw about five dozen similarly sized, freshly interred graves.

All the while Tania’s in-laws never forgave her for being Russian. They never forgave their son, either, for marrying one. And she had no news of her own family. Once arriving in Antibes, she’d begun sending frequent letters home but she heard nothing. She assumed her parents and siblings had perished. The only response she received was from the French police. Why did she send so many letters written in Russian?

It was some five or six years later when Tania received a response. Her parents, sister and youngest brother were still alive! Mirka will tell me later that Tania’s family had lit a candle for their daughter every Sunday. They’d been sure she no longer lived.

But Tania’s two older brothers had perished at the front. They were young men. One had joined the Air Force and died from complications following a crash. The other brother went missing in action.

Her brain time travels again. Tania recalls, with evident clarity, the last time she saw her brothers. Her eyes fix on this vision. The boys were in the army, marching in their military uniforms in front of her school. The troops sang Red Army songs. Tania stood with her schoolmates. One brother waved to her. It’s her final memory of him. She scrunches up her eyes and mops the tears with her handkerchief.

Je dis trop, Tania says. I say too much. The memories are too vivid, even after generations have passed, but she doesn’t hold back. She wants to share her story. Philippe reaches across the table and touches her clasped hands.

Postscript

The tables do turn for Tania. She and Pietro will raise two sons and a daughter in their home on Chemin des Mougins. She’ll return to Krasnodar and her Cossack village, venturing out solo on July 18, 1968. She recalls the date precisely. Her five-year-old sister, now 32, will run out of the family home to embrace her. Three years later Tania will return to her Cossack homeland again, this time driving all the way from the Cap d’Antibes with her husband and two of their children. Together they also will visit the Kerch catacombs, a section of which becomes a tourist attraction. And in a supreme reversal of roles, the German factory owner one day will visit Tania and Pietro, driving to the Cap d’Antibes in a camper van.

Today Tania’s front room on Chemin des Mougins is sprinkled with pieces of modern life. A large, flat-screen TV occupies pride of place atop a wall cabinet. Beside it lies a boom box. Tania’s son works in Antibes’ Port Vauban and visits daily on his scooter. A granddaughter lives next door, serving as the guardian of a large, Russian-owned estate.

Pietro passed away five years ago, but his name remains on the postbox, just as a fine gold band remains around Tania’s ring finger. Her home – once owned by her in-laws, and the same Cap d’Antibes walls she has occupied since her arrival in France just after the war – is situated on the estate managed by her granddaughter. Grace flows two ways. The Russian owners have given Tania the right to occupy her home for the rest of her days.

By the strength of her character, that could be for a long while.

Read the whole story:

Very well written and most interesting ! I enjoyed reading Tania’s unique story! And Iam happy for Tania that It is now saved In your written words! thank you the hours you spent to so do! ?

Thanks so much, Marie-Claire. I also felt strongly that Tania’s story needed to be told and preserved. One Swedish author-friend has mentioned the idea of an ebook, just to have it available to interested folks. j

Bonjour je suis une des petites filles de Tania , merci pour ce livre , ces histoires qui on bercé mon enfance , les récits de ma grand-mère on toujours été captivant mais je viens aujourd’hui vous apprendre son décès a l’âge de 100 ans 🙏 c’était la meilleure grand-mère du monde

Bonjour, Karine, et merci beaucoup-beaucoup pour votre note. Je suis vraiment désolée pour le délai ridicule de ma réponse – et surtout d’apprendre le décès de Tania. Votre grand-mère était une femme formidable, forte et gentille. Elle avait des sentiments profonds; elle avait un grand cœur. Ce fut un grand privilège de passer du temps avec elle et d’entendre son histoire. Merci d’avoir envoyé ce message.

What a gift you have given to many of us by writing Tania’s story! We have lived comfortably for generations since war of this sort has not devastated our land. It’s almost impossible to comprehend how just surviving was so encompassing . It’s an honor to read her story. It makes me more appreciative of how blessed my life has been and I need to remember that! Thank you to you and Philippe for your gentle and in depth reporting!

Merci, Mum! It was an honor for us to meet Tania. Survival was definitely the recurring theme of these years in her life. I’ve been cleaning out every leftover in our fridge for the past couple weeks until finally Philippe said, “Enough already!”

How lucky for Tania and for us that you took the time and interest to recount her amazing story of survival. It is unique to her but also reminds us of other survivors during this terrible time in world history. I was interested, especially, in Kerch. My grandmother was born there and came to Chicago in 1903 at age 8 to escape Czarist tyranny.

Thanks for your story, Barb. Yes, Tania’s recollection is an example of many, and I’m betting many readers will have parallel stories running through their minds as they read. Interesting that yours shares that city of Kerch. Thanks for jotting a note here. j

Thank you! I too feel it would be a wonderful service to publish this wonderful piece so that even more people could read and understand what those difficult times meant for so many. This was so well done.

The ebook is on the “to do” list. Thanks for the nudge, Mary!

What an amazing story and so well written Jemma. I am myself, a product of WW II: in 1944, after being wounded, my father was brought back to Canada and to the military hospital, along with some of his fellows of combat, including his friend Hector, who was my mom’s brother. And it is while visiting her brother that my mom met my father. And I was born in 1945. So my presence on this planet is another collateral consequence of WW II.

I was so totally engrossed in Tania’s story you told for us – aside from the ridiculousness and the horrors of war, I am always caught by the evidence of such resiliency and courage of people like Tania – and how lives are lived and families are forged from such terrible circumstances. I think our students who study history would be captivated by Tania’s story and her memories- so vivid all this time later.

Thank you so much for sharing – and how interesting to read the replies your faithful readers shared!

Thanks to you, too, for continuing the dialogue, Deryn. Resiliency and courage: such hallmarks over the generations! As for studying history in school, it only comes alive, I believe, through story. I spent too many years calling it my least favorite subject of all. j

Thanks, Andy. Isn’t it great how one story can resonate with so many, and in so many different ways! I appreciate your contribution to the conversation. j

Bonjour je suis patrick un des fils de tania merci pour avoir raconter cette partie de ca vie ,moi même j ai toujours trouvé qu cela mérite un véritable livre et pour nous c est maintenant chose faite en partie, je viens de lui traduire rapidement le texte et elle était très émue et heureuse MERCI encore de la part de toute notre famille

Patrick Laveder

Je suis très contente de recevoir votre commentaire, Patrick. Je m’excuse pour mon français, mais j’ai bien voulu que l’article a plaît à votre mère et à sa famille. Elle est une femme généreuse avec un grand cœur et une mémoire très vivace. Son histoire a touché beaucoup de gens. J’ai fait imprimer le texte ce soir et je l’ai mis dans la boîte postale de votre mère. Je l’ai aussi envoyé une photo par la poste il y a quelques jours; j’espère qu’elle arrivera. Merci encore fois pour me prendre contact.

Oh my goodness – HISTORY, or in this case HER-STORY, and what a story it is. This is how it truly comes to life, just riveting, and please if you have time before you head off

THANK HER AGAIN on behalf of all your readers, for a profound and beautiful tale of strength, love and survival.

Absolutely, Tracy. You may see in the above comments that Tania’s son has translated the piece for her. What a pleasure it is for all of us to know that this magnificent lady, and her family, are all happy with the words – and that they will keep her story alive through the generations. Strength, love and survival, indeed.

Thank you, Jemma and Philippe, for another wonderful story on French Lessons. Truly a moving and important piece of local history, beautifully rendered in your blog. Merci!

Merci bien for your note, Chris. A true joy of basing ourselves here for long periods is that we can make these connections. Another joy is sharing them. So glad to have you experiencing everything alongside us this summer. j

J’ai été fascinée par le récit de la vie extraordinaire de Tania. Je suis pleine d’admiration pour son courage et sa détermination qui l’ont aidée à survivre et à surmonter toutes ces épreuves.

Merci d’avoir partagé avec nous, lecteurs, cette fabuleuse histoire !

(Pour Patrick s’il me lit : c’est grâce à Pascal que j’ai pris connaissance de ce texte, c’est une histoire presque incroyable.. Je pense que toi et ta famille êtes très fiers d’elle.)

Merci beaucoup, Michèle. Je suis très contente que vous avez m’écrit. Je suis encore plus heureuse d’apprendre que le monde autour de Tania peut prendre part à son incroyable histoire. j

I was very moved by the story and its telling. Jemma vous etes un vrai raconteur.

Merci beaucoup à Electa – and to all of you for adding your voices to the song that underlines Tania’s story. j