The penny dropped in the back seat of an Antibes taxi.

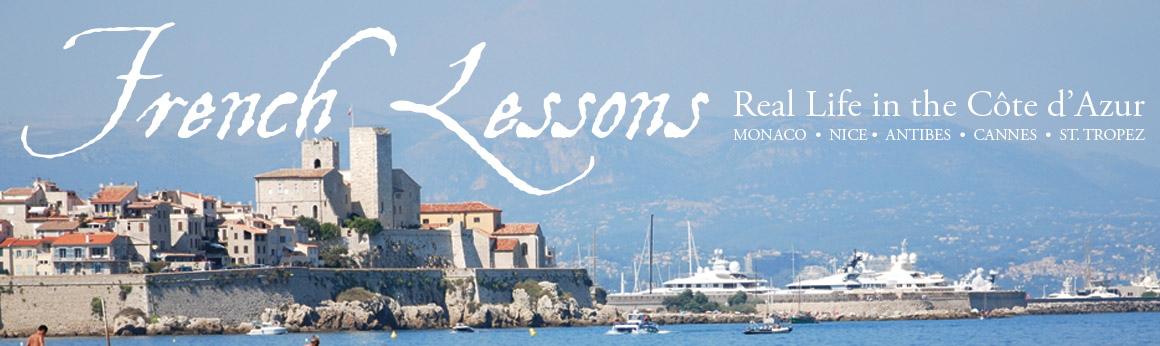

The fact that five-year-old Lolo and I were driving around our former hometown in a taxi should’ve labeled us as tourists, particularly in this seaside town situated midway along the celebrated Côte d’Azur.

But it wasn’t exactly the taxi ride that gave me this new appreciation. It was the conversation with our taxi driver as we journeyed away from the stand. She declared that she knew me. I knew her, too.

A busy, intervening year faded quickly.

Est-ce que vous avez un enfant qui va à l’École St Philippe? Does she have a child attending the school St Philippe?

Oui.

Bingo. Tall and sculpted, with long sandy hair and a prominent jaw line, she was the mother I always thought should be modeling Ralph Lauren sportswear. Instead – I’d had no idea – she drove a taxi.

Votre enfant s’appelle Marcus. Your child is Marcus.

Beside me in the back seat, Lolo’s eyes bulged. She whispered to me more audibly than I liked: “She’s the mommy of the scary boy?”

Her words were packed with meaning: Our taxi driver is the mommy of one of the three tough boys from my maternelle class the year before last? But you promised me all year long, whenever we talked about returning to France, that I’d never, ever have to see that boy again!

The taxi’s radio called Marcus’s Mommy at a very fortunate moment. I hope and believe she missed Lolo’s question. But as our taxi journeyed down Boulevard Albert 1er and onto the seaside road that leads to Bellevue, our home in Antibes, the situation prompted my new, big idea in returning to this town: That our family will never again be tourists here.

I’d feared that even after living here for a full year – even after enduring a tumultuous winter and sending my only child into a full-on, French maternelle – I feared that we’d still be classed as tourists after a year’s absence. Relegated to the suite of Anglophone visitors who journey to this celebrated shoreline for some beach and sun.

To the contrary. In these initial moments back in Antibes, I’m realizing that distance has somehow cemented relationships. It’s as if people now say, “Hey, if these foreigners go away for a year – perhaps sending the intervening email or two – and then come back to town and look us up, they actually ‘mean’ it.” There’s some dedication in the relationship, even a thought that we derive mutual value in maintaining our friendships – perhaps growing them.

Taking the pulse of this seaside town took about a day. By then I was au courant on the local news:

- Economics: Fabienne, my esthetician, was moving on. As I wished her luck in her next venture – perhaps she was starting her own salon? – she shrugged her shoulders and said, “au chômage.” Tomorrow she’d be unemployed. An English esthetician at another salon later told me Fabienne was taking all of July off work. That was the problem in France, the Englishwoman said. People care less and less about employment. They’re happy to live off state benefits.

- Politics: In the tireless row over whether Ikea would be allowed to open an outlet just north of Antibes, the mayor of Mouan-Sartoux trumped the mayor of Mougins in a Paris tribunal. Ikea’s hopes were scrapped – at least in this round. The Frenchman’s soul belongs to le terroir, to the soil. Commerce must not change its face.

- Social: A good half of Lolo’s former maternelle classmates still remembered her, a year on, as she and I joined parents in collecting the pint-sized pupils at the end of classes. Lolo batted her eyelashes at young Eros, the winged cupid who over the last year had become her petit ami. She’d just forgotten to inform him of the happy news. Fortunately Eros’ sweet mother laughed as I explained my daughter’s girly outburst.

Knowing the fabric here also helps in dealing with local characters. As Lolo and I re-discovered Antibes’ cobbled Old Town that first day, we found the carousel closed at the prime hour of 3pm. Its aluminum siding was locked firmly in place, and the little painted ticket hut was slapped shut. The attendant we knew from last year, an easygoing chap with shaggy, salt-and-pepper hair and glasses perched on his nose, was nowhere to be seen. I enquired with a man at the nearby kiosk for Antibes’ tourist train.

Je ne peux pas vous comprendre, he told me. I cannot understand you.

I sank fleetingly into a funk that my French had lurched violently southward over the last year, despite enduring studies at the Alliance Française in Toronto. Then I tried to think like a local.

First off, I’d goofed. I’d forgotten the necessary greeting: Bonjour, monsieur. Or alternatively something flashier like, Excusez-moi pour vous déranger, monsieur, mais…. Excuse me for disturbing you, sir, but…. Now I had two options: Create a shared problem (unlikely here), or make a joke.

I asked again, a bit more loudly, about the carousel’s re-opening. Then I looked at my watch. “It’s 3:00!” I said with sudden drama. “The man who works there is probably having a very good lunch!”

The train man laughed. He hardly had an answer about the carousel attendant’s whereabouts – but no Frenchman admits a lack of knowledge about anything. One thing was for certain, though. This man understood my French.

As the ultimate sign of not being tourists in this place, our family was invited into a Frenchmen’s home just a couple days into our stay. As a culture, dinner parties have stronger roots in North American households. During our prior, year-long residence on the Côte’s shores, the homes we visited for meals were those of other immigrants – of people from England, Wales, the US, Canada, Bosnia, Iraq and Lebanon. Not of folks who were born-and-bred French. (Our few French invitations centered around four-year-old birthday parties.) Part of this dichotomy reflected the natural course of our friendships; part of it was cultural. French friends gathered in cafes or restaurants – or at our house.

But now we were headed into the hallowed quarters of a French family – people whose daughter attended school with Lolo – for an aperitif dinatoire.

For an aperitif? A dinner? I had no clue. Neither did my French-Canadian husband.

The aperitif dinatoire turned out to be various wines and finger foods. But that’s not the point. What matters is where we shared this meal. We four adults sat in the tidy front room of a real French family’s home. Lolo bounded around the corridors with Clotilde; she was expected to roam more of the house. At one point, just to ensure the crayons hadn’t strayed from the papers, Philippe and I nipped into the further reaches of the home – much against protocol, I recently learned from Polly Platt’s well-read book French or Foe? But there we were, inside the closed doors of the French family home. We are hardly tourists anymore.

After this productive start, our little family left town. We cruised the Greek Isles. We visited England. And now we’re back in Antibes, opening our own doors to two Canadian families who will stay through mid-July. We are at home, and actively absorbing how little of life’s routine has changed:

- Roman Abramovich – the Russian oligarch, Chelsea Football Club owner and lord of Château de la Croë that graces Cap d’Antibes’ promontory – is back. Floating gracefully in the bay outside our home when we returned from Greece was the newest boat in his personal fleet, a sleek 377-footer called Luna, including her two helipads and onboard beach club.

- “Our” sunbather, as Philippe calls her, has returned, too. She’s the lean, jet-haired woman with a tattoo on her right shoulder who makes the rocky beach outside Bellevue her sun worshipping mecca every summer. Oh yes, did I mention she’s topless? Philippe heralded her appearance as I returned from shopping the other day. He was mopping his brow after an observational interlude on Bellevue’s sea-facing balcony.

- Mr Marc also paid a visit. A frequent subject of this blog space last year, Mr Marc personally re-engineered Bellevue’s wonky air-conditioning and heating system. He could’ve taken up residence here last year as the seasons changed for the worse. But as ever, Mr Marc is never far away. On the muggy day after we returned from England, as we set up residence in Bellevue for the summer and prepared for the arrivals of visiting families, the air-con in the TV room conked out. Mr Marc’s arrival in Bellevue’s corridors only signaled life as usual – life in the non-touristy world – for our family in the Côte d’Azur.

But there was one thing – a single occurrence since returning to our past lives in Antibes – that convinced me we’ll never again be tourists in this part of the world. Life, in an innocent and sweet way, has come full circle.

When Philippe and I first visited Antibes – that momentous stay during which we’d stumbled on the skeleton of a house we now call Bellevue – it was October 2005. Lolo was seven months old.

We ventured into neighbouring Juan-les-Pins one afternoon, Lolo plastered to my front in her Baby Bjorn carrier. As we ambled down the main street, the ice cream in a shop called Pinocchio was too dreamy to pass by. Philippe and I each had a cone, and in a moment of lapsed fatherhood, Philippe requested a taster spoon of vanilla ice cream for Lolo, who had just begun to take strained (non-dairy) foods. As Philippe put the spoon to Lolo’s baby lips, her legs began to flutter. They began to kick. She pounded me with all her baby force. “More! More!” she seemed to scream.

I’ve blamed my daughter’s enduring passion for ice cream and the entire genre of desserts on this single encounter, her first taste of real sweetness. Often when we’ve passed Pinocchio over the years, in the car or on foot, I’ve told her of this experience.

Fast forward to this week. In a perfect example of the deferred way in which friendships can blossom after a significant pause, we hosted a handful of Lolo’s school friends and their parents for swimming and a potluck dinner. Among the guests were the five-year-old heartthrob Eros and his mother Samantha.

She brought ice cream – tubs of chocolate, vanilla, lemon, mango and cassis. She juggled ice cream demands effortlessly. She scooped balls from the tubs with great mastery. From the banter around the table, I gathered she did this regularly.

Samantha scoops ice cream every day. It is she and her husband who own the famous Pinocchio.

When it was my turn for ice cream that night, I chose vanilla. I let the coolness melt slowly on my tongue. As the children chased each other in our garden, the ice cream tasted all the sweeter.