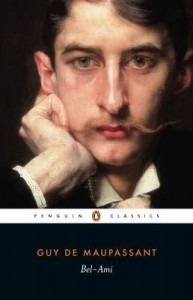

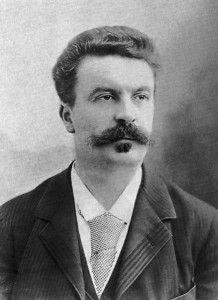

Last autumn I took a French class in Toronto in which we read Bel-Ami, a novel by Guy de Maupassant. At the time, I hardly knew that the author ranked among the most famous authors of the Belle Époque.

Nor did I realize that he spent the winter of 1885-1886, right after Bel-Ami’s publication, in our summer hometown of Antibes.

Nor – and I figured this piece out with a great deal of luck – that the famed de Maupassant stayed that winter in Villa Muterse, just up the hill from Bellevue, before our house was even built. And Villa Muterse, I should add, was the ancestral home of Edouard Muterse, the chap who built our Bellevue in the early 1920s.

At least I think that’s the case anyway. It’s the truth according to a booklet written about our neighbour, the Port de la Salis.

Whatever the reality, the history behind Bellevue’s birth appears to be an interesting one. Throughout our five years here, the house has generated a good deal of interest from long-time Antibois, hopeful acquirers and mere passersby. So I figured our grande dame was ripe for a bit of genealogical probing.

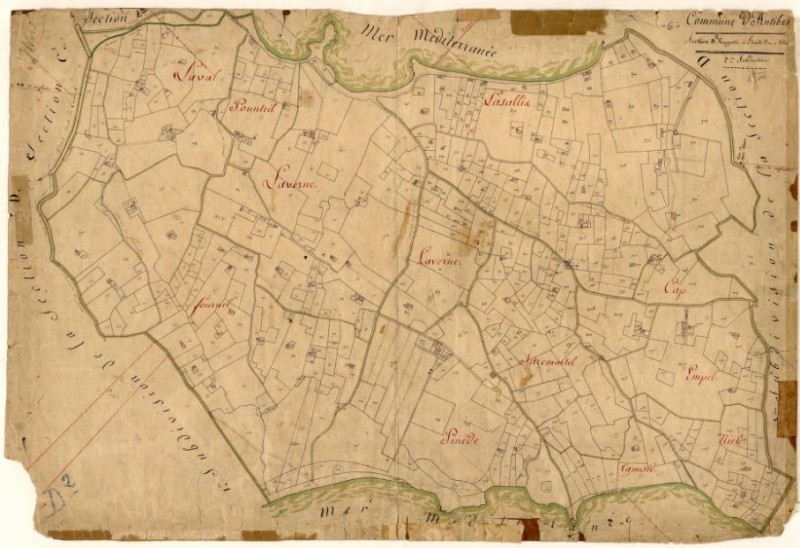

Wednesday afternoon I found myself in the lofty, brightly-lit Archives Municipales d’Antibes. On the welcome desk two stems of pink orchids gave life to a space otherwise stacked with books and files.

The receptionist immediately called for assistance. A young woman appeared from the doorway at the back of the room. She wore a tank top and jeans and thick, rectangular glasses, and had a tight, stubby ponytail.

I was hoping to discover the history of our house, I tried to explain. My French sounded more halting than usual, probably because I expected this French bureaucrat to shoo me back home for some non-existent paperwork before agreeing to talk further.

On the contrary, Emilie was happy to do some research. And here, without an appointment or any documents related to Bellevue, I managed to swamp this young woman’s Wednesday afternoon. She was either innately helpful or, I thought excitedly, keenly interested in my case.

Emilie consulted that same booklet on the Port de la Salis. She dipped into digital maps. Armed with preliminary details, she headed into the back room.

“The documents are heavy,” she said. “I’ll only return if I find something interesting.”

I flipped through books at the back of the Archives Municipales while the raspy-voiced receptionist and her colleague played videos at the front of the room. As time passed, I discovered that Edouard Muterse, my supposed father of Bellevue, was the son of Maurice Muterse, Antibes’ historian – and small world, I already knew it was Maurice, way back in the 1880s, who taught the novelist de Maupassant how to sail his yachts.

Conversely, Edouard Muterse was into the social services. In the early 1930s, he was Président of the odd-sounding Bureau d’Hygiène Sociale. Then again, I learned, the years between the wars were tough ones in Antibes. At times, running water was a rare privilege in this city by the sea.

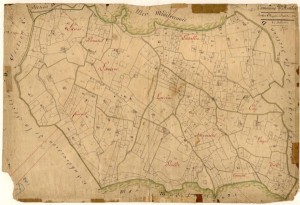

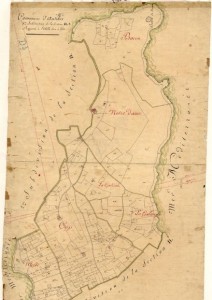

Eventually Emilie returned with two enormous, fabric-bound books. Their spines were broken, and their yellowed pages were soft and torn. She opened one of the volumes to a page entitled “Mallet”. The text was handwritten, inscribed with exacting flourishes in old-fashioned ink. She shared her notes:

In 1824, the parcel of land on which Bellevue stands was part of a large holding by a farmer called Jonche. He sold it a couple years later to a gun maker called Rey. The land passed through the ages in this way, eventually belonging to Rigal, the storied banker from Cannes who swept into the Cap in the early 1880s with grandiose ideas. Five years later Mallet, a diplomat, bought the property. He still held it in 1914, a fact that corresponded with the tattered tome on the table. But then the thread disappeared.

Could the lack of information relate to the beginning of a world war? I asked Emilie.

“Non,” she replied quickly, pursing her lips. I should have no worries about the administration of this data. She skipped out for a cigarette break and returned to suggest that we look at photos given to the Archives Municipales by the Muterse family.

A black-and-white photo of Edouard himself popped up on the computer screen. Taken around the turn of the century, he was in his early 20s, seated on a straw chair with his hands resting on a cane. He had a thick crop of dark hair, a straggly beard and long, twisted moustache. A pair of metal spectacles balanced on his nose. If he shaved off the forest of facial hair, I thought, young Edouard might actually be a good-looking guy these days.

The photo’s caption labeled him as the stately Jean Baptiste Joseph Edouard Muterse. He was born in Antibes and died here, too, in his villa Le Bosquet – the very place up the hill that welcomed the novelist de Maupassant all those years ago.

Emilie returned to the handwritten volume of land listings that lay open on the table. “I’m fed up,” she said. “I’m missing something.” But the end of our day had come. I thanked her profusely. It was nearly 5:00pm, and the Archives Municipales closed at 5:00pm. Sharp.

The next morning I returned to the Archives with Bellevue’s compris de vente, the sale agreement. Oddly enough, Emilie was pleased to see me. She still wore jeans and a tank, her hair pushed back tightly from her head, thick rectangular glasses bisecting her face.

The compris didn’t help one bit, so she returned to the original booklet about Bellevue’s neighbouring port. At the back was a list of contributors. Emilie pointed to Denis Aussel‘s name.

“He still lives in Antibes,” she said. “His father’s about 85 now. He might be able to fill you in.” In fact, Antibes isn’t large. There are a lot of people here, Emilie said, who remember the past.

She made a couple phone calls – the people on the other end of the line were obviously intrigued – and returned to say that that Aussel lived at – get this – Le Bosquet. The home Edouard owned, just up the hill from Bellevue. The building once called Villa Muterse. The very place where de Maupassant stayed one winter. It turns out that through marriage, the Muterse family line lives on in Le Bosquet today, under the family name Aussel.

Again, the end of our time had come. It was noon, and Emilie’s work at the Archives Municipales ended at 12:00pm. Sharp.

I have yet to officially link Bellevue’s creation with the Muterse family, but I’m keen to do so. They’re an interesting cast of characters who are engrained in Antibes’ own family tree. The Muterses are a breathing example of the French passion for le terroir – their land, and the centuries of culture, tradition, ideals and beliefs that are churned into this land.

And the deeper I dig, the more profoundly the Muterse roots sink into le terroir just up the hill. Guess which door I’ll be knocking on next.