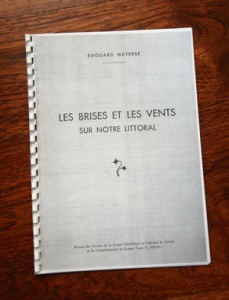

When Jean Aussel and his wife first set foot in Bellevue – coming here to tell us the story of our home, while also allowing Jean’s wife the chance to revisit her childhood abode – one of the first things he did was hand me a simple gift. The photocopied pages were spiral-bound and entitled Les Brises et Les Vents sur Notre Littoral. The Breezes and Winds along our Coastline.

Hardly a page-turner, I know. It was an extract from the annals of the learned Société Scientifique et Litteraire in Cannes, dated 1939-1941. But on closer look, I understood the relevance of the gift. The author was Edouard Muterse. The man who built Bellevue.

“He sailed a lot,” Jean said, giving the motivation behind the text. “He had many sailboats in his life. You could perhaps get up in the morning at a good hour, and you could look at how the wind rises, and the light … so he wrote this,” he said. “And it explains Lou Gargali – it’s a Provençal name – for the morning wind….”

Lou Gargali: That’s the name Edouard gave to Bellevue – until some unknown person decided to change it.

As I read the opening lines of Les Brises et Les Vents, Edouard’s character seemed to jump from the page. A colleague, he wrote, asked him to share his personal observations from his long practice of sailing navigation along this coastline, and “je n’ai pas cru devoir refuser.” He believed he ought not refuse. Edouard’s phrases were stately yet conversational, sweet yet erudite.

Jean flipped to the back of the booklet. “Et voilà!” he said. “The man who constructed your home!” It was the same black-and-white image Les Archives Municipales had given me a couple weeks earlier. Edouard was probably in his 30s, with a thick crop of dark hair, a straggly beard and long, twisted moustache. If he shaved off the forest he might be quite handsome.

Now Jean Aussel, Edouard’s grandnephew, and his wife were sitting in our living room. That the octogenarian was sipping from a chilled glass of whiskey only suggested that his stories might become more prolific.

We already had an inkling that Edouard Muterse was a generous man, largely through stories from Jean’s wife (see 30 July 2011). He’d kitted out Bellevue (or shall we now call her Lou Gargali?) with lovely china as part of the rental package (and oddly, that very set, through marriage and inheritance, has returned to Jean’s wife own kitchen cabinet). We also learned that Edouard offered his own property as home base for the local Girl Scouts.

Jean Aussel’s opening description of Edouard was as a “vieux garçon.” An old boy. That’s a way of saying that Edouard Muterse never married. He never had kids.

“Edouard Muterse was the brother of my grandmother,” Jean said. “He was a lawyer. He never married, but he was un homme trés raffiné, trés sympatique, trés agréable” – very elegant, very likeable and very pleasant.

He was born in 1878 at Le Bosquet, the house up the hill from our Lou Gargali, and the very place where Jean lives today. Edouard studied law in Aix-en-Provence, where he became a lawyer in the Court of Appeals.

“He was un homme trés attachant – a very captivating man,” Jean said. “You’re an intelligent woman” – he said this presumably because I hounded him with researched questions – “so you would’ve liked this Edouard. He had quite the sense of humour. He played cards – he played bridge. When my mother played cards with him, she’d come home at night and we’d ask her, “What did Uncle Edouard say?” He always had a joke.”

When World War I broke out, Edouard was in his mid-30s. He served in the Chausseurs Alpins, an elite mountain infantry of the French Army, and was shot. While recovering in a military hospital in the countryside, the man recuperating beside him was the parish priest of Gonfaron, a little village in Provence. The curé was, of course, also a vieux garçon. The two men struck up an enduring friendship.

On occasion, the curé visited Antibes. He came here – and Jean indicated right here, the rocky beach just below Lou Gargali – where young men and women would swim and sail and basically make merry. The curé saw these young women in their bathing suits and, as a priest in the 20s might’ve done, he got anxious. He had to blot out these ideas. So the curé from Gonfaron found a nearby path with cattails growing on either side. The cattails formed a decent wall against women in risqué swimsuits. He perched there, gazing upward toward the Chapelle de la Garoupe, his Bible in hand.

Edouard and his sense of humour hardly let that image go. Jean gave a bit more background before continuing the story. “My uncle actually had a lot of money,” he said. “He had a very easy life, so he bought a nice sailboat and an American car – the first American car before the war – the Hudson (pronounced “HOOD-son”) Terraplane.”

So one time – this was the first half of the 1930s – Edouard and le curé drove the HOOD-son Terraplane for an aperitif in neighbouring Juan-les-Pins, a town that was making headlines for inventing waterskiing and inspiring Coco Chanel’s first suntan. It was here, too, that the current female fashion statement was les pyjamas.

“They were un scandale, les pyjamas, because they hugged the buttocks,” Jean said, curving his palms toward us in a polishing motion. So right there, in 1930s Juan-les-Pins, three pretty women wearing les pyjamas passed in front of the curé from Gonfaron with their buttocks bien moulées. Edouard didn’t miss a beat. He called out to the waiter, “Garçon! Garçon! The cattails! The cattails!”

“Like this, you see the life of Edouard Muterse!” Jean said amid our chuckling.

After serving in World War I, Edouard couldn’t bear the horrors of Aix-en-Provence. He lived close to the square that housed the city’s guillotine; the gruesome device was still in use. Worse, people kept asking Edouard if they could watch the executions from his home. It shocked him, so he moved to Marseilles.

But Edouard often returned to Antibes, to Le Bosquet, to visit his father who’d become a widower at a very young age. In this part of the world, family homes traditionally pass through the generations. Nowhere is that more true than at Le Bosquet, a provençal home that has remained within a single family since it was built in the mid-1700s. Edouard moved definitively into the storied residence when his father died in 1928.

That’s about the time that Jean Aussel put on Lou Gargali’s birth – the late 1920s or even the early 1930s. It was somewhat later than I’d expected. Edouard Muterse, he said, built our house with money he’d earned on the sale of land on Cap d’Antibes. While the Cap today is covered with apartments and villas, back then the peninsula was largely wooded and full of scrub. Sizeable tracts of this fallow land belonged to a few wealthy families.

But times were changing. It was the beginning of Le Front Populaire: Sweeping social reform within France brought the first, paid holidays. Meanwhile, Antibes’ mayor favoured development. In 1920, Edouard donated 460 square-meters of coastal land for the development of our neighbouring Port de la Salis. Between 1925 and the beginning of World War II, he sold great stretches of wooded properties between Lou Gargali and la Garoupe, another Cap d’Antibes shoreline.

As Jean spoke, the penny was dropping. Edouard Muterse never actually lived in Lou Gargali. He built our home for rental income. Part of me was glum that the man never had occupied our home. But at the same time, I was thrilled to occupy a small part of Antibes’ long and storied history, in a house built by one of the city’s most enduring and notable families.

Meanwhile, Edouard’s own home up the hill was always open. ”Because he wasn’t married and he was quite an engaging man, everyone – all the Antiboise – called him ‘Tonton Edouard’,” Jean said, “as if he was their uncle.” Uncle Edouard received lots of visitors. He had a trés belle library, Jean said, and he collected succulent plants that he exchanged with “the whole world.”

As if I needed to root Lou Gargali even more deeply into the history of Antibes, Jean described another of Edouard’s possessions housed within the welcoming Le Bosquet: the so-called Galet de Terpon. The oblong stone dated back to the 5th century B.C. Inscribed upon its surface was the oldest Greek inscription found in the whole of France.

“C’est extraordinarire,” Jean underlined, as if I hadn’t already figured that out. It was Edouard’s father, Antibes’ historian, who helped bring the discovery to light. When Edouard died, his family contributed to their French inheritance tax assessment by selling the Galet de Terpon to none other than the Louvre.

Which basically brings us to the end of this tale. Or is it just the beginning?

The preliminary research and this encounter with Jean Aussel only has drawn me further into the Muterse rabbit hole. The name Muterse jumps off library book pages at me like the beacon of the Garoupe lighthouse, up the hill from Lou Gargali, pierces the nighttime sky. Antibes’ library holds more books written by Maurice Muterse, Edouard’s father – and even a couple entries by Edouard himself. There’s an Avenue Muterse up near the train station. The Galet de Terpon today resides in Antibes’ Musée d’Archeologie. Of course I’ve paid a visit.

The list continues. Each discovery is a celebration of connection. It’s a tribute to lives long past. Time paves over their stories unless we stop to unearth them.

A few days after the Aussel visit, Philippe lunched with a local friend at Le Plage Provençal in Juan-les-Pins. He mentioned my research of all things Muterse and the fact that Bellevue once was called Lou Gargali, supposedly after a particular morning wind. Moments later he met the Provençal’s boat master, a deeply tanned, local man of 60-ish. People here would call him “un vieux loup de mer” – an old sea bass. An old salt.

(The vieux loup de mer’s father, as it happens, was the previous boat master at the Hôtel Provençal. Rumour has it that he was the one who invented waterskiing. And so, quite relatedly, this tanned, 60-ish man that Philippe met began waterskiing at age six and instructing at 12. In his teens he was France’s national champion.)

Ben oui, the vieux loup de mer knew about lou gargali! It was a cold wind that arrived in the early hours, he said, when fishermen were pulling their nets out of the water. It didn’t come up often, but when it did, it scared them.

Philippe explained that the man who built our house also loved the water, and that he called the place Lou Gargali. But someone, sometime changed its name to Bellevue. General consensus that lunchtime was that Lou Gargali was a better name. Antibes and Juan-les-Pins already had too many Belle-’s.

So, Philippe asked me that evening as we prepared our meal, now that we’ve stopped to unearth the past: Should we switch the name back?