“C’était dommage,” Jean-Claude says, shaking his head piled with thick waves of white hair. It was a shame, he says, but “mon père a voulu absoluement l’acheter, et ce Monsieur Rigaud n’a jamais voulu la vendre.” His wrinkled face forms a playful smile around startlingly blue eyes. Jean-Claude chuckles a little after explaining that his father really wanted to buy our home Bellevue, but the owner back then didn’t want to sell it.

The fact that this 74-year old in a magenta-and-white checked shirt is here, chatting with Philippe and me at our home along Antibes’ broad bay, is something of a dream to me. He is a newly discovered link to Bellevue’s storied past.

I’m dying to see the photo album he had tucked under his arm when he arrived with his son Olivier, who owns a gourmet chocolate store in town, but the album lies on the terrace table alongside bowls of olives and pistachios. The photos will have to wait. For now we’re walking through Bellevue’s main rooms, heading on a trip down memory lane. I carry my phone everywhere, having asked permission to tape our conversation as, I say, my English is a little better than my French. The two men agreed, laughing charmingly.

The geography of our home has changed, I’m learning. It has undergone something akin to the shuffling game played with three overturned cups. Jean-Claude surveys the work we did on Bellevue some eight years ago. Our living room was his boyhood dining room. The room we call the dining room was closed off and used as an office. Completing the circle, our office was his living room.

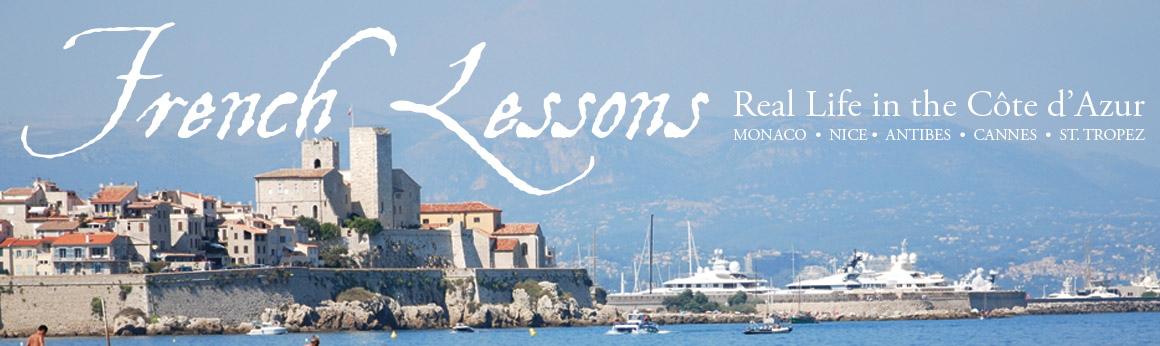

But the old plan made sense, Jean-Claude explains as we move onto Bellevue’s wide terrace, the hub of our existence here even if it’s exposed to the elements. He understands why we did what we did to the terrace – the view is quite exceptional, sweeping from the city’s sandy beaches to the ancient old town with the Italian Alps forming a scenic backdrop, at least on clearer days – but this space was closed during his childhood. Its exterior wall looked like any other.

We pause here at the edge of Bellevue’s terrace on this steamy afternoon. Waves from the Baie de la Salis trickle onto a pebble beach beneath us. The thick air is engulfed by the throbbing hum of the season’s cicadas. Jean-Claude surveys Antibes’ bay and its sandy beaches from this perspective, both new and well-known to him.

“Cette plage est artificielle,” he says. The sandy beach is fake; the sand is all imported. In his day it was rock, like the rest of the coastline around here. Pebbles and algae. So much barer was the terrain back then, he says, indicating the wide crescent of coastline that leads between Bellevue and the town, that his mother would aim a set of binoculars over the land to spot his father as he walked home for lunch in the midday heat. Today you could confuse a single man with a couple hundred other people – and that’s assuming you could make him out in the first place against an unbroken backdrop of apartments.

Jean-Claude raises a finger with a new recollection. His blue eyes sparkle against his round, lined face as he studies the rocky jetty at the neighbouring port. At nighttime, he says, he and his brother Philippe would build shallow pools off the jetty with six-holed bricks from the nearby shipyard. In the morning, once the tide had gone out, they’d find the pools populated by minnows. Des petits poissons! he says with evident joy, holding the tips of a thumb and forefinger four inches apart.

The minnows will hardly be Jean-Claude’s most startling recollection from his childhood at Bellevue. He lived here between the formative ages of 7 and 16. It was just after the war when his family moved in as renters – 1946 to be precise. In fact, one of the first things Jean-Claude said when he walked through Bellevue’s door was that he’s not from here. He’s not a true Antibois; he wasn’t born in Antibes. Now we get the detail. It was his grandfather who lived in Antibes at the close of the war, and he was the one to encourage Jean-Claude’s father, a lawyer from Burgundy, to head south with his young family. This, Jean-Claude’s grandfather told them, was where the action would be.

Longer readers of French Lessons will remember that two summers ago I devoted several posts to the puzzle of Bellevue’s origins. In the end I traced the roots of our grande dame to 1930, give or take, with her vision originating from Edouard Muterse, a descendant of the area’s notable Guide family. Edouard had rented out this property by the sea, and I stumbled on one of her earliest occupants, Arlette, a women who – amazingly enough – became a relative of Edouard himself, though several years after his death in 1948. She married Edouard’s grandnephew a decade and a half after having lived in Bellevue as a child.

Arlette’s family, the Caus as they were called, had moved to Antibes from the north of France to escape the great war – but they were forced out of Bellevue earlier than they’d liked. By the early 40s, the war had descended onto Antibes. With Bellevue’s strategic, shoreline location, the Italians requisitioned the home. Unsurprisingly, the details of what happened within her thick, stone walls during the occupation years are sketchy at best. Arlette mentioned that Bellevue’s garage was mined. A local man and longtime member of our neighbouring port told me the structure, once a proud home, had been ransacked by fleeing troops. They ripped everything of value from Bellevue’s frame, pipes and all.

Other than that, we only knew that Bellevue stayed within Edouard’s descended family until sometime in the 1950s or 60s. Being childless, Edouard left the property to his niece, but her husband – a banker named Rigaud, the very one mentioned by Jean-Claude a few moments ago – insisted that they hang onto the property as an investment. What happened from that point until the mid-1960s has remained a mystery.

Jean-Claude, the septuagenarian standing on our terrace today, is the answer. He’s more than the answer given the stories that populate his memory. He knows the strength of this next one before he begins it. It’s a staggering image that, given the way he holds court with Philippe, his son Olivier and me, he seems eager to share.

His gaze shifts down into Bellevue’s garden. Today it’s a verdant plot, punctuated by a couple palms, a parasol pine and a couple smaller varieties. Our daughter’s wooden climbing structure occupies one stretch, and in the middle lies an iridescent, turquoise swimming pool.

This story about our grande dame by the sea is his earliest, one that actually happened just before his arrival here as a child. It was late 1945. After a couple insufferable years, the region was once again free territory. Jean-Claude explains that the first task at Bellevue for his grandfather, the man who’d beckoned his family south, involved German prisoners. These last words stun me.

“Revolver dans les mains,” Jean-Claude continues, “ils déminaient le jardin, car le jardin avait des mines.” There were mines everywhere. His grandfather had the German prisoners in his sight, down the barrel of the revolver, à quatre pattes – crawling – through Bellevue’s garden, routing out landmines.

The picture is so visual it both thrills and horrifies me. Philippe and I find ourselves repeating virtually every word to make sure we heard Jean-Claude correctly. Des prisonniers allemands? Un revolver? À quatre pattes? Yes, we have understood.

Once the land was mine-free, a process Jean-Claude insists didn’t take terribly long, Bellevue was like a small hotel, at least by today’s standards. Her occupants included Jean-Claude’s family – father, mother, Jean-Claude and his younger brother and sister – and extended family that stayed full-time as well. The brother of Jean-Claude’s mother trained at the legal offices of Jean-Claude’s father. The other siblings of Jean-Claude’s mother also lived here. And then in the summer months, the brother of Jean-Claude’s father arrived with his family of five, bringing the grand total under Bellevue’s roof to 14 people!

“C’était ma mère à l’époque qui faisait les courses à bicyclette,” Jean-Claude says. His mother did the shopping for all these people on her bike. The group ate meat two or three times a week, he recalls. Fish was on Fridays as a matter of good Catholicism. And otherwise meals focused on eggs or soup, and there were always two types of vegetables, often laced in sauce. And cheese. Of course there was cheese.

Philippe and I are trying to accommodate all these inhabitants within Bellevue’s current framework. Jean-Claude explains there were five bedrooms on the garden level as opposed to our three. And up top, there were four chambres rather than two today. I grab my phone, which still records our words, and together we climb Bellevue’s circular, marble staircase to survey the changes.

As we reach the top of the steps, Jean-Claude pauses. This was his bedroom, he says, indicating the landing and a great circular hole that plummets three stories to the basement. Yes, his bedroom led out onto the upstairs balcony. His room was here, right here. It no longer exists.

It was, funnily enough, exactly what Arlette had told us of her own childhood bedroom when she visited Bellevue for the first time a couple years ago. Fortunately from neither former occupant have I perceived a sense of loss.

I still marvel at how we found Jean-Claude; it is a manifestation of the world remaining small in these parts. News of his existence first came through our local friend Veronique, mother of one of Lolo’s former schoolmates. Her family also sees Dr L, the kind and sociable family doctor we’ve visited from time to time since purchasing Bellevue eight years ago. Dr L apparently told Veronique that he knew someone who had lived our home. My mind boggles at how, exactly, the three-way connection among Veronique, Jean-Claude and us was determined through Dr L (what with client confidentiality and all), but then this would hardly be the first time I’ve heard talk about a third party from our amiable doctor friend.

Jean-Claude, Olivier, Philippe and I return to Bellevue’s terrace and seat ourselves around the dining table. Philippe breaks open some sparkling rosé while we, the hosts, seem to be devouring most of the olives and pistachios. The buzz of the cicadas ceases only momentarily now and then as Jean-Claude answers our battery of questions and summons his most vivid memories. At last we break into the photo album that he carried with him through the front door.

A mosaic of black-and-white photos decorates each broad page, bound by a clear cover. Some depict clean-shaven men in ample suits and women in primly collared shirts and abundantly gathered skirts. Others capture the grins of a little blonde girl and her slightly older brothers. Jean-Claude’s brother Philippe, we learn, became the show waterskiing champion of the world shortly after the family moved from Bellevue. Each photo and story is enchanting in its own way.

But rifling through the pages, the other character regularly present in this family’s lives was the grande dame herself. Bellevue’s office was filled with plush, rectangular furniture and pleated, ceiling-to-floor draperies. We learn that in front of the home, where today we park cars, was a badminton court – just as we purchased a badminton set this summer for our garden below. Bellevue’s garden, instead, was home to a ping-pong table on the coarse, dusty earth beside the seawall. And where we dug a rectangular pool, there was an enormous, cylindrical urn – the sort that in ancient days would’ve carried olives and their oil to market – with thick, leafy branches poking out at the rim. The urn sat atop a tall, marble platform where in one photo – similar to the antics of our own daughter today – Jean-Claude’s sister had climbed for a pose.

On a whim I head inside Bellevue and pick up a white dessert plate decorated in a red, pink and grey floral motif in the art deco style. Back on the terrace I present it to Jean-Claude.

Philippe helps me explain the plate’s significance. It was a gift from Arlette and her husband Jean, who felt – much to our delight – that it belonged here. This plate was one in the service Arlette had used as a girl in Bellevue. It had been reunited with her rather circuitously after she married into Edouard Muterse’s family.

But the little plate means nothing to Jean-Claude. His family rented the home unfurnished, unlike the let during Arlette’s day. Evidently Edouard Muterse managed to get his belongings out of Bellevue before the house was requisitioned in the war. Jean-Claude’s family had to bring their own furnishings, big and small.

“C’était incroyable,” Jean-Claude says, returning to his pet subject. He shakes his round head lightly. The injustice of it all seems a bit incredible. His father wanted to purchase Bellevue in 1955, but the banker Mr Rigaud didn’t want to sell at that time. So in the end Jean-Claude’s family bought a home on the other side of the Cap d’Antibes in Juan-les-Pins, and they moved there.

Jean-Claude’s family evidently had fallen in love with Bellevue and her idiosyncrasies – but the grande dame’s journey continued in the mid-50s without Jean-Claude in it.

His life in Antibes has blossomed over the decades, even if he doesn’t consider himself an Antibois. He specialized in tax law and knows well certain people in our circle – such as the famous Jean-G and Madame Double-Barrel featured in this summer’s earlier blog posts. The small-world story of Antibes carries on.

But other mysteries remain. Jean-Claude knows our home as Lou Gargali, the baptismal name given by her creator, Edouard Muterse. Someone changed her title along the way. Someone, too, added a sculpted frame to her front door with the initials “RC” and a beautifully carved, cherubic angel on the overhead mounting. I continue searching.

But this day, out of the cracks of time, a local man – the father of the guy who owns the fancy chocolate store in town and a guy who doesn’t consider himself a true Antibois – has filled in a nine-year gap about our Bellevue. This gentleman easily could’ve sat next to me in a café last summer, or five summers ago, reading his newspaper and drinking his morning coffee.

Now, as I wander through Antibes’ old market or buy bread from the boulangerie, as I get my hair trimmed at the salon or sip more coffee at a local café, I will wonder who lingers beside me – today, or perhaps tomorrow.