Seventy-five years ago, in the later stages of World War II, the Côte d’Azur escaped the grip of Occupation. The wave that brought Libération into this far southeastern corner of France came from the west.

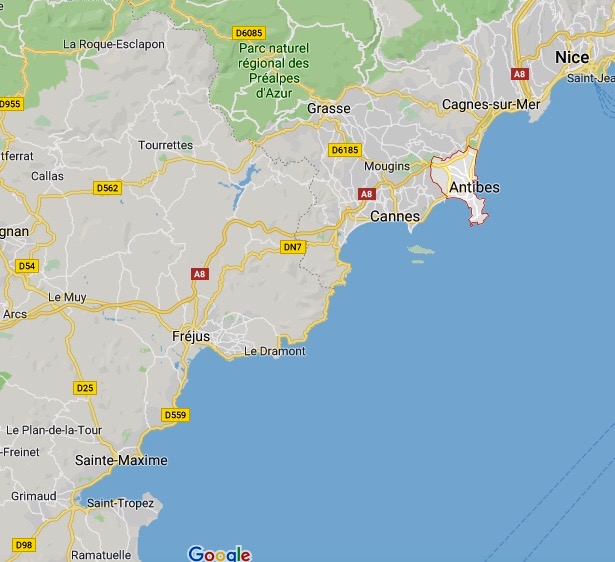

The operation began on August 14 and 15, 1944, when tens of thousands of Allied troops flooded the coastal and mountainous regions around St Tropez. The forces fanned out, some heading west, some inland, and some eastward. One group of Americans followed the Mediterranean coastline in the direction of Antibes, our summer hometown. They would release one town from the enemy’s grip and move to the next, creating a chain of events that foretold future moves.

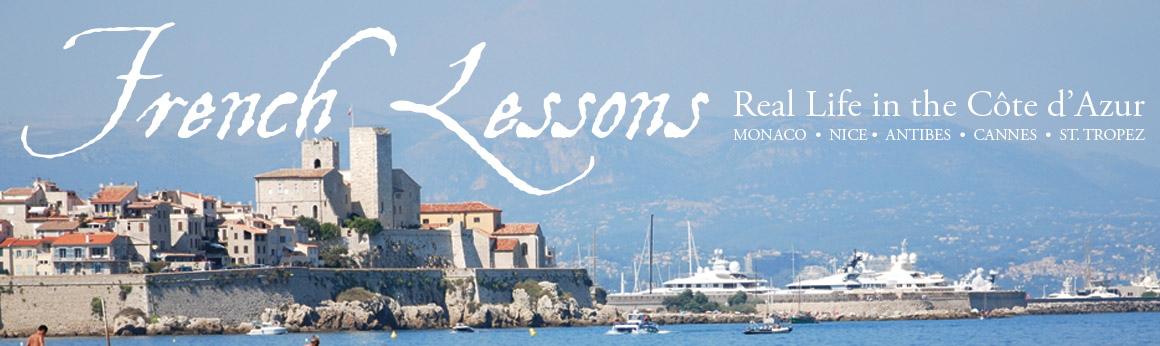

The Antibois followed the developments on national radio broadcasts transmitted out of La Brague, a district in northeastern Antibes beside the Brague River. One night, when the Americans had pushed some 40 kilometers eastward into the well-defended town of La Napoule, the enemy pummeled Antibes’ main harbor. Whole chunks of its stone barrier crumbled, and with it fell the lighthouse. Debris littered Antibes’ docks, boats, beaches, and waters. Days later, German aircraft bombed the century-old lighthouse at the top of Cap d’Antibes. As the detonation resounded into the Salis Bay, local fishermen looked up from their rods and watched their city’s principal beacon tilt and collapse.

Town by town, the approaching Americans pushed back the Germans, but it was Antibes’ local Résistants who played the starring roles in this city’s Libération. After years of Occupation, first by the Italians and then by the more meddlesome Germans, Antibes had lost a quarter of its population. Among the remaining 18,000 residents, an important underground movement spread across about 20 branches of larger organisations. The Résistants’ weapons were a slapped-together collection of machine guns, revolvers, rifles, and shotguns, with hardly enough ammunition to go around. The 400 or so patriots knew they had to act with great caution – but they also faced an enemy with waning morale. The Germans were still reeling over the D-Day landings up north in Normandy ten weeks earlier. As American troops paused 12 kilometers away from Antibes in the city of Cannes, most German posts in Antibes remained occupied, but a couple hours before the fateful August 24 began, the enemy began to trickle out of Antibes.

It was with this background that Antibes gained its freedom. To mark this 75thanniversary of Libération, French Lessons shares details it has gleaned over the past decade from websites and books and the local archives municipales. Except for The Riviera at War: World War II on the Côte d’Azur, a passionate tome written by our former neighbour George G Kundahl, the material in this blog post stems from French accounts. For the sake of general interest, the words are much distilled from the available detail. We can’t promise dissertation-level accuracy (and please put us straight in the comments section), but we’ve sought to gather the story from the streets during August 24, 1944, a pivotal day in the history of Antibes.

Overnight: Le Capitaine Vérine, codenamed “Gustel,” judged the moment was right. For years the Résistance had remained clandestine as it gathered intelligence, published underground newspapers, and facilitated Allied arrivals into the area. Now its members would go public. As head of the secret army and the local sector of the Forces Françaises Intérieures (the newly organized collaboration of Résistance fighters), Gustel defined the FFI’s imminent mission: To rebel against attempts to destroy Antibes’ essential services (e.g., water, gas, and electricity) and its communications network (e.g., rail stations, bridges, and transmitters).

6:00 a.m.: Dawn arrived. Antibes had not burned in the night. Mines at the electricity plant, the water company, and the central post office had been diffused before they could explode. One casualty was the PTT [Postal, Telephone, and Telegraph] office in neighbouring Juan-les-Pins. Also destroyed in the night were the bridge and communication lines crossing the Brague River.

The Résistants moved into the second phase of their mission: To neutralize or destroy the enemy stationed within Antibes, and to officially take power by seizing public buildings.

8:00 a.m.: The uprising began. About 30 groups shared the responsibilities. One team spread into the German’s nerve center at the Red Cross, in the inland Terriers district of Antibes. Another group swept the Fontonne and Brague areas, while others pushed into Saramartel at the mouth of the Cap d’Antibes, where the enemy still manned its bunkers, ready for action. One team took charge of the port and Fort Carré, while another went for Antibes’ train station and the electricity plant. Other groups headed toward the docks and the so-called “Casa d’Italia” that once sheltered the Italian Gestapo. Still other teams occupied Antibes’ post office, its mairie (the seat of the local government), and its barracks. A final group oversaw the resupplying effort.

10:00 a.m.: As the purge continued, the Comité de Libération met at Brasserie Jules at the top of Rue de la République, the spine of Antibes’ old town. The bar was once known for its Beaujolais soirées and the occasional strip-tease, but now it was the rendez-vous of the Résistance. As the committee gathered at Brasserie Jules that momentous morning, crowds began to demand the seizure of Antibes’ mairie.

A long procession formed along Rue de la République and began to march into Antibes’ old town. The people united their voices in “La Marseillaise,” France’s national anthem. Eventually they reached Place Nationale and then swerved left at the circular fountain having a granite sphere at its peak, at which point they attacked the gradual ascent of Rue Georges Clemenceau. The crowd amassed themselves outside Antibes’ stately mairie, a broad building with a circular clock and iron bell at is crown.

Gustel and other Résistance leaders entered the mairie and strode to the office of Jules Grec. “M. Le Maire,” Gustel addressed Antibes’ mayor, “je suis le chef – I am the chief of the Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur, designated by the responsible leaders of the Comité d’Alger [a provisional government of Free France under Charles de Gaulle]. In this position and according to received instructions, I ask you to hand in your resignation as mayor.”

The maire agreed. The transfer of power had taken place, and the Comité de Libération was in charge of Antibes. Gustel asked city employees to continue in their posts, and a pharmacist took on the responsibilities of mayor.

Noon: The Red Cross nerve center had been cleared of occupying troops, but the manned bunkers at Saramartel on the Cap d’Antibes brought a greater struggle. As the August heat soared, several dozen German soldiers were taken prisoner. The population, sensing its freedom, put out their flags. The festivities began.

1:00 p.m.: “Ils reviennent! They’re coming back!” The cry began as a rumour and grew more precise. The enemy had pushed into Cagnes-sur-Mer, a coastal town 10 kilometers north of Antibes, and approached Antibes from the opposite direction as the Allies. The Germans now drove along the main road toward the train station at Biot, which stood just over the Brague River from Antibes.

The Antibois panicked and pulled in their victory flags. Gustel hastened his best response, ordering the Résistants to erect barricades on the major roads leading into Antibes. Meanwhile he sent couriers in the opposite direction, toward Cannes, to seek help from the Americans.

2:00 p.m.: A van packed with German militiamen barely escaped a minefield at Biot’s station and made an about-face. A half-hour later, a German patrol forced its way into the hills occupied by Antibes’ Résistants. French revolvers met German machine guns in the only serious conflict of Antibes’ emancipation.

Some German fighters rushed into a bunker at Biot’s station. The rest were repelled by the Résistants, who had been bolstered by local reinforcements. An hour later the Germans tried again to break into Antibes. A truck of enemy soldiers brought lively gunfire, but the menace retreated, zigzagging toward a small fort in Villeneuve Loubet, some kilometers away. It would be the German’s last attempt.

6:00 p.m.: Feeling they’d eliminated the present dangers, the Résistance leaders drew up a plan for the night. Their conference was interrupted by a courier: The first American soldiers were rolling along the road from Cannes toward Antibes.

Antibes’ flags appeared again, covering the city. The population emerged from their homes and lined the streets to announce the Allies’ arrival.

7:00 p.m.: Joy surged through Antibes on the arrival of a column of American parachutists. The detachment of 50 men and several tanks paraded through town, distributing a precious gift of chocolate. The troops took up position at La Brague, on the edge Antibes where the enemy had returned only a few hours earlier – but the Allies seemed to push out of town as abruptly as they’d arrive. Their eastward drive continued.

Antibes’ celebrations continued into the night. Nine Antibois had lost their lives that day. Some died defending their city, and other casualties were youth wielding grenades taken from German warehouses. For most of the population, though, it was a moment to revel in new-found freedoms. There would still be outbreaks of fighting after the close of August 24, 1944, but this date would remain the dividing line between Antibes’ Occupation and its Libération.

Today we can spot this history in small doses. At the edge of Antibes’ old town runs Avenue du 24 Août. It leads nonchalantly past a movie theatre, a comic strip shop, and a bus station before ending at the top of Rue de la République, where Brasserie Jules has become Café Pimm’s. The bistro’s croque monsieurs, citrons pressés, and pichets of rosé are of the moment, but the flamboyant deco signage, and the faded tromp l’oeil façade portraying a French carousel, speak of yesteryear, and delightfully so. Meanwhile, lying just beyond Café Pimm’s, spanning out from the Rue de la République, is an open plaza. The Libération procession once crossed the same space singing “La Marseillaise,” but today the square has a new name: Place des Martyrs de la Résistance.

Every now and then, too, we’re reminded more dramatically that WWII crossed these shores. Last month the authorities closed Antibes’ Salis beach. Shortly, a couple military trucks arrived from Toulon, 135 kilometers from Antibes. The vehicles’ exteriors announced their purpose: DÉMINAGE. Bomb disposal. Fortunately, divers only found a corroded gas canister.

Thank you for sharing this important piece of history!

Hi Jemma,

I was 7 when Antibes welcomed the American and I can still remember the joy and happiness in the whole town. (I had plaits at the time and my mother had adorned them with bleu, blanc rouge ribbons !). Commandant Vérine’s daughter, Damiène was a neighbor and school friend of mine and I used to go and play at their place. I remember him (and his dog Vertrix ) as a very nice person but of course I never would have thought he was such a hero !

Thanks for reminding me of those special moments.

Michéle

How fortunate we are to share your firsthand recollections, Michéle, alongside these acquired stories. Damiène, Vertrix, and those patriotic plaits: You’ve moved my breakfast table as I read aloud this morning. Thank you.

Jemma, thank you sincerely for this passionate, concise, and vibrant insight into the WWII history of Antibes. I feel now like I was there as a witness! Beautifully written.

xoxo Shelley

You are welcome, Shelley! It was a bit of a labour of love.

This was fascinating- what a wonderful historian you are. You may have a 3rd or 4th career in writing so well regarding the war. Thank you for a well-researched account.

It was so interesting to learn about Antibe from a historical perspective and showing us where it all happened. Thanks for educating us about the Liberation.

I always admire how France honours the specific dates and heroes of the war, as well as the liberation. Thank you for filling in some fascinating backstory.

Hi Jemma: What a terrific, detailed account of the liberation in Antibes. Thank you for sharing this.

Un plaisir! Thanks to you, too, for treating us to your weekly blog!

Sorry for the delayed response…a riveting account.

That was very informative and interesting. Thanks

Merci, Alex! V nice to have comments amid isolation!

Great read! And thank you. it is sad there is no mention of who took part and who was responsible. I’m delighted to say that the bar you mentioned was held by my father as hq where Polish officers would find my father to get them to London to fly the spitfires etc… my father’s army were mostly Polish and a few resistance and British SOE’s. There is just too much to mention. But I must state that Commandant Camille Rayon ALIAS ARCHIDUC Winston Churchill’s Secret Army and a SOE was in charge and responsible for the liberation of Antibes and the region La Paca from Marseille to Menton. I have official documentation to support this. Before the allies had disembarked most German officers would find my father anf would order thousands of their German soldierd to put there arms down as this would be the protocol that my father would guarantee to get the German Officers the honours safely back to London. No shots were fired!

I’d be delighted to share this with you!

What a delight to hear from you, David! I most certainly know your father’s name: Commandant Camille Rayon, alias Archduc, populates countless volumes of Antibes’ WWII literature. Thank you so much for including his name and these details here. It is a joy to have your personal connection and insights. Stepping back, I am stunned to think how many lives your father changed with his bravery and leadership. Merci for reading this post and for taking time to pen this reply – and the following one. I’ll be in touch directly.

You also mentioned General Kundahl who I met some years ago he read a book written by John Goldsmith SOE accidental agents and wanted to meet my father which we did organise over a period of time The General Kundahl a retired desert Storm during the Gulf war father Bush… Had written a 15 page résumé of my father over 500 missions accomplished and detailed based on facts and official documentation.

I’d be delighted to share this!

What a detailed account……last month I tried to find the house where my mother lived with her parents in 1920s and 30s….we had estate agents details of the house near Antibes railway station. There seemed to be postwar housing and we couldn’t find the house. Was that area bombed at liberation?

Hello Wendy, and I do apologise for the ridiculously tardy reply – especially as I understand you’ve taken time, as I have, to research the Antibes area. From my own reading, I understand there was some destruction in that area especially as troops moved west to east out of Antibes during Libération, but I would not want to be taken as an authority. The archives municipales are a fascinating place if you like research; they helpfully pulled out cadastre after cadastre for me to trace, as best we could, the lineage of our Bellevue. The results were not definitive, but the process has been very rewarding.

Hi Jemma, how kind of you to reply at all! I’m afraid my poor French would not be up to tackling The archives in Antibes…it was an interesting holiday project which we enjoyed..perhaps one day we will go back! I will try to send you a post card of my mother’s house just in case you might be interested . Greetings , Wendy